In the 2000s, Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical comic (she prefers this term over “graphic novel”) Persepolis became an international sensation. The title refers to the ancient capital of Persia, the first multinational empire in history.

Drawn in gloomy, contrasting black and white style, the French artist recalls her affluent but violent childhood in Tehran in late 1970s and early 1980s. Volume 2 of the story is the chronicle of her teenage years in Austria and her return to Iran in 1980s and 1990s. She co-directed the movie adaptation, which was nominated as Best Animated Feature at the 80th Academy Awards in 2008.

Marjane was born into a middle class family with a maid and a Cadillac. Her Marxist parents influenced her worldview when the uprising against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi began in 1978. The Shah resigned and left Iran, and the communists were freed, including Uncle Anoosh. Meanwhile, Iranians worried about the rise of Islamism and Marjane’s friends began to move to the United States. The communists were murdered by the Revolutionary Guards and Uncle Anoosh was executed as a “Russian spy”.

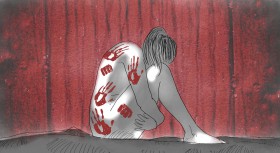

The nightmare continued as Iran went to war against Iraq and women were ordered to wear the veil. The women decided to fight back, but the demonstration was the day when Marjane saw people being beaten and killed with her own eyes.

In school, a cult honoring the war dead as “martyrs of the revolution” grew and Marjane led her friends mocking the rituals. Adult Iranians also tried to rebel with more dire consequence. Parties went on despite the fear of air raids, but the bigger danger was the Revolutionary Guards – the angry young men who had the power of dragging citizens outside their homes just because they were suspected of deviating from Islamic values.

At 12, “Marji” began skipping classes and flirting with boys, which created tension with her mother. Meanwhile, the Islamic Republic refused cease-fire, and so she took smoking to deal with teenage angst and the state oppression.

The stress of playing cat-and-mouse with the Revolutionary Guards (not to mention the rising cost of bootleg tapes and jeans) peaked when Marjane’s Jewish friend Neda died in an air bombing. She pushed the principal trying to seize her jewellery, and in her new school she spoke up against the teacher’s propaganda. A daring act, but her mother reminded her of the consequence: an imprisoned woman wouldn’t be executed as long she’s a virgin, so she would be married with a guard, who would take away her virginity and then kill her. Her parents decided it was impossible for her to stay in Iran and sent her overseas – to Austria.

Marjane did not last long in her first home in Austria, as her friend’s family was pretty bitter about their downgraded lives in Europe. Her foster mother put her in a convent, where she honed her drawing skills and read books on anarchism and Simone de Beauvoir. She was expelled after eating a pot of spaghetti in the TV room.

She felt the awkwardness of living among the sexually liberal Europeans, and coped by adopting a punk-ish identity and smoked joints. She was less lucky in love, as her dates either came out of the closet or put her in the friend zone. Meanwhile, she was tired of being yelled at by Austrian women looking down at her, including her landlady Dr. Heller and the mother of her boyfriend Markus.

On her 18th birthday, tragedy struck. Marji missed her holiday train and wanted to surprise Markus, only to find him with another woman on his bed. She left Dr. Heller’s home and lived on the streets, until bronchitis almost killed her.

The only option was returning to Iran, wearing veil again. The war had ended with nothing changed. Again, she had a hard time adopting, saw psychiatrists and tried suicide. She entered university and studied graphic arts, where, during anatomy class, the female model wore full-body gown ,and she was warned for looking at the male model. Amid the double lives of elite Iranians (veil outside, wine inside), she agreed to marry her boyfriend Reza, who was her polar opposite in personality.

For their final project, Marjane and Reza created a plan for an Iranian theme park, inspired by Iranian heroes and myths. Having graduated with the perfect grade, Marjane pitched the theme park to the city hall only to face the truth: the Islamic Republic is not interested with its pre-Islamic past.

The end of the theme park was also the end of Marjane’s marriage and she was accepted into The School of Decorative Arts in France, where she now lives. Despite the setback in Austria, Europe is more suitable place for her, and she’s prepared better to leave Iran for good.

The second part of Persepolis resonates with me, who after years of being comfortable with Australia, felt hatred for the lucky country and found myself lost on the supposedly familiar streets and society. I also thought of suicide for relatively trivial reasons and saw the campus’ counsellors. Like Marji, I also felt a disconnection with old friends after returning home and got confused on why little progress was made in the country where I grew up – and why even some things went worse.

According to Satrapi, the lesson of Persepolis is every country could go down the path of Iran. It could have happened to us in 1999. This is a theme that keeps us worrying throughout this decade. Several revolutions failed to create better governments in the Middle East, and our neighbors are trying hard to prevent changes from happening.

On a more personal level, Satrapi’s story has helped me deal with my past trauma and tells me that sometimes you have to return – to your home or to your spiritual home – in order to move on.

You can order Persepolis online through Books & Beyond, Kinokuniya, or Periplus.

*Illustration courtesy of Riley Citron

Read Mario’s take on Indonesia’s irrational fear of communism and follow @mariorustan on Twitter

Comments