I never planned to become an avid collector of Indonesia’s traditional textiles. In fact, I used to hate them. Being half Batak, a North Sumatran ethnicity, I am more exposed to my mother’s robust culture because my grandparents, uncles, aunts and pure-blooded Batak cousins all live the capital. (My father is from Sumbawa).

As a child, the rectangular, hand-woven ceremonial cloths called ulos reminded me of the torturous, lengthy Batak weddings and funerals. Mourners don a piece of ulos as a shoulder cloth, and the most sacred type of ulos is often used to partly cover the deceased. It was too morbid, too depressing.

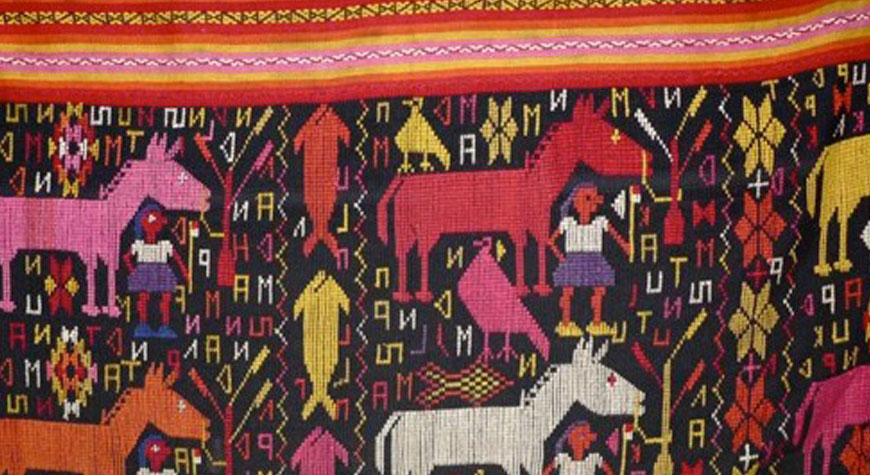

Things changed in 1998 when a friend introduced me to textiles from Timor Island and their playful designs depicting animals, insects and humans. Then I bought books on Indonesian textiles. More than 15 years later, I have more than 300 textiles from various cultures and islands. “What are you going to do with your rotten textiles?” asked a dear Sumbawan friend. You will find the answer later.

I am sure you are familiar with batik from Java, where patterns are created through a painstaking process of hand-drawn wax design and repeatedly dipping the textile in different dyes. Before the brouhaha about the origin of batik erupted a few years ago, when many Indonesians suddenly became so patriotic, I already collected batik.

But Indonesia is not all about batik.

Some ethnic groups in Sumatra, Kalimantan, Bali and Sumbawa produce fabulous cloths that require weavers to alternately insert gold threads in perfect order to create patterns in a technique called songket.

The ikat technique is mostly associated with patterned cloths from Sumba, Flores, Timor, Sulawesi and the Moluccas. It requires the threads to be tied and dyed then carefully woven, taking care to line up the patterns in the threads so that the design is clearly visible. It’s complicated, isn’t it? Prized textiles from Sumatra may even combine the songket and ikat techniques and embroidery.

A textile can have so many meanings. In Iban territory in West Kalimantan, a man would take enemy heads as a sign of bravery before the Dutch banned headhunting in 1920. For an Iban woman, weaving can also be an expression of going to war. An inexperienced weaver wouldn’t attempt to create dangerous patterns such as serpents because they believe the spirits could attack them and make them ill. I am proud of my small collection of rare Iban textiles.

Should you collect textiles? It depends on your passion – and your bank balance. It’s an expensive hobby and I am constantly bokek (broke). But I encourage you to explore the immense variety of textiles from across Indonesia.

Maybe you can hang a textile from your parents’ cultures in the living room? Don’t be a cheapskate and don’t buy printed batiks made in China, no matter how gorgeous you think they are. A handmade batik can take months to finish. It deserves some respect.

If a weaver from Timor tells you that she has to spend hours and days wrapping knots of threads around the wraps between passes of the weft to create patterns that strike your fancy, do you really have to bargain hard? The technique called buna is so complex that a piece of sarong can take a year to make.

Back to the question from my Sumbawan friend -- what I am going to do with those textiles? I cherish them, study them and my plan is to bequeath them to my nieces. It’s already in the Will.

About Lewa Pardomuan

Lewa works for an international news agency, is spending too much time on Facebook, loves to travel, collects Indonesian textiles and other artifacts, and hates lousy Indonesian restaurants in Singapore.

Comments