They say your earliest memories usually involve pain. Mine was getting my thumb stuck in a tiny doll shoe the whole day and having my dad eventually cut the shoe with scissors. It wasn’t so much a physical pain as it was an infantile sense of failure and embarrassment.

I must be around two years old at the time. Then there was that time I fell off my wooden horse after rocking it too hard despite my mother’s warning. The worst part was I had to suppress my cry because I knew it was my fault – another pride-related pain.

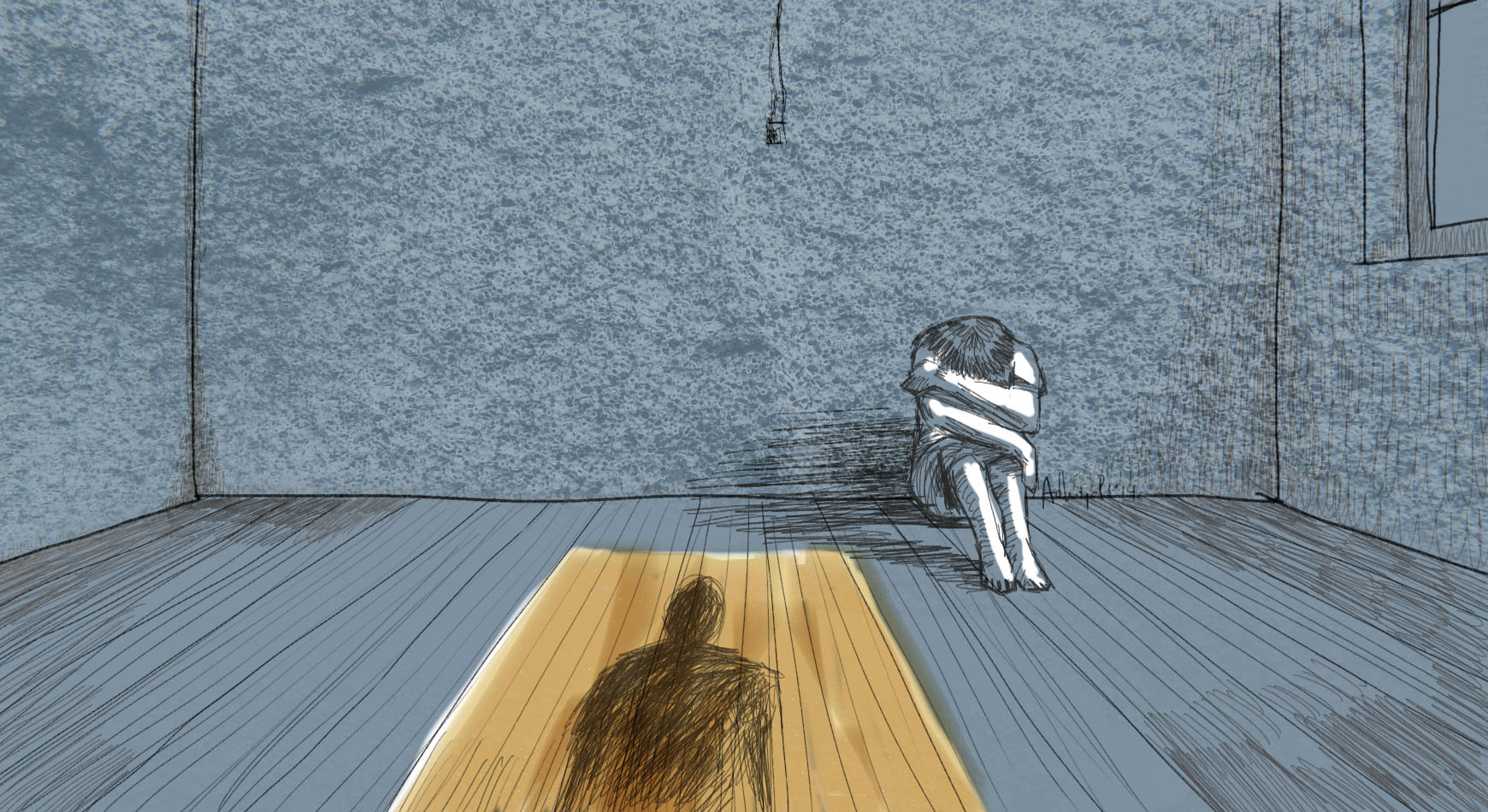

But the real childhood pain that occurred in a certain period of my life was not easily recalled for many years. The memories had been long buried, locked in a mental box of things that kids would rather forget – the traumas manifested subconsciously.

When I was about nine years old, I woke up frozen in fear in my bed one night because somebody had taken over my body. It wasn’t late at night, but the house in a small town in eastern Indonesia, where we were living at the time, was empty, because my family had gone to a night fair. I had wanted to go, but apparently I fell asleep, so they left without me.

This boy was in his teens. My parents had taken him in when we moved from the previous town to help his impoverished family, who had taken care of my parent’s land. My parents gave him home and sent him to school, while he helped around the house. He was a friend to me and my three siblings, a smart boy who could charm everyone with his jokes.

That night, I woke up to the presence of him peering over and doing things to a part of my body that I thought was not supposed to draw other people’s attention. I lay there, stiff as a rock, pretending to sleep while wondering what was going on. I knew it wasn’t good, but my cowered instinct told me fighting him might not end in my favor.

I didn’t tell anyone about that incident, but I should’ve, for it wasn’t the last time. Back then, when I woke up in the middle of the night and couldn’t go back to sleep in the bedroom I shared with my sister, I often moved to my parents’ room. In the morning, though, they rose earlier than me. And while my father was getting ready or having breakfast and my mother was busy in the kitchen, I sometimes found myself awakened in their bed by the feeling of something moist and musky on my lips. The boy had kissed me and then walked away casually when I opened my eyes in horror, as if to let me know that I was his possession.

By then I was no longer scared of him, at least publicly. In fact I treated him just as I did before, so that nobody would suspect what had happened. I was ashamed of being found out. However, in those mornings in my parents’ bed, his disgusting taste still lingering in my lips, I was angry with my parents for failing to protect me, for getting up without waking me, leaving me at the mercy of this boy again.

Later as I grew bigger and after he had been sent back home (not sure why, but it wasn’t because of me), there was another guy, older this time, who took over his place. He was a brother of our housemaid's who helped out around the house while our family paid his schooling.

About 11 years old at the time, I often woke up in the morning feeling his presence in my room. I’d then close my eyes pretending I was somewhere else, mentally blocking any suspicion of what he might have done to me while I was asleep and forcing my mind to bear the next few minutes until he was gone.

It strengthened my conviction that there was no safe place in the world, or, rather, at home. My sister and I always locked our door when we slept, but this would happen during the windows of time she was outside of the room in the morning.

I still didn’t tell my parents. I thought the fact that I had been singled out by these two guys meant there must be something wrong with me. I prayed that if I kept quiet everything would turn out OK. And just like with the previous boy, I acted normally around him, even playing chest (my favorite pastime at the time) with him to mask the dirty fact that I was a weakling, his prey.

Unearthing the Truth

Later as our family moved again, and the guy stayed on in that town to finish college (he eventually found work in a bank, a job that my father helped secure), everything went back to normal. I grew up like other teenagers, and I continued my studies in the United States.

.jpg)

One day during my university years, a TV program on child sexual abuse I happened to watch unleashed the flood of memories. It struck me that I had been sexually abused all those years ago.

Suddenly it explained why I could never sleep in an unlocked room, why a certain part of my body had seemed untouchable, why I was always wary of male domestic helps in my family’s home, and why I did the ritual of checking if my bedroom door was locked three to five times before I went to bed every night.

And it would eventually become clear, why, despite the carefree life that I had carved for myself overseas, I still felt as if I had no voice sometimes.

It wasn’t so much anger that I felt than sadness and disappointment that my parents never knew, even suspected it. The next time I went home for holiday, I told my mom about my childhood experience. It was followed by other shocking revelations from my two sisters too. My mother cried and my brother vowed to kill those guys. We all had a good cry that day.

Looking back, that day was the beginning of a new me. I still check a few times if my bedroom door is locked before I go to sleep; you will never catch me voluntarily sleeping in a dormitory-style shared room; and when I’m in bed alone I sometimes wake up at night in cold sweat, feeling like someone is in the room with me. But I have largely moved on.

My mindfulness practice has helped me navigate through my seasonal dark moods, the inexplicable sadness and the creeping feelings that I am never safe anywhere. I keep my life simple and fulfilled, and in return I don’t harbor hates of anyone, even my abusers.

I have accepted this part of my life with the kind of calmness that shock people sometimes. When the subject of child sexual abuse came up among close friends, I could casually tell them that I, too, was molested as a child. This seeming nonchalance often leave them speechless, unsure how to respond. I can feel them seeing me in a whole different light. But I am done with keeping secrets, because I had done nothing wrong.

The spate of child molestation cases in Indonesia that emerged in recent weeks has led to the assumption that people who were sexually abused as a child will turn into pedophiles themselves. This is an unfair generalization. Throughout the course of my life, I’ve personally and closely known more than a handful of men and women who were sexually abused when they were young. We all have a seething hatred of child molesters. Evil has not made a predator out of us. Yes, there may be cases of victims-turned-abusers, but they are in the minority, and other factors often play a role.

What the abuse has done to me, instead, is develop a state of hyper awareness of how easily children can be sexualized. When my nieces and nephews were young, I was often worried when they had to be alone with drivers, servants or gardeners, or any man or older boys. At public places, I wonder about the intention of men who touch kids too much.

This is what I have been trying to do, raising awareness among people I know of how vulnerable children are to sexual abuse, so they educate their kids about the threat and make sure to keep them safe from sexual predators.

I came clean here, resisting the option of using a pseudonym, because I want you to know that I’m not ashamed. Being a victim of sexual abuse does not define me, though it has shaped me to be who I am.

Most importantly, though, I have a voice. It’s never too early to tell your kids that they do too.

Follow @dasmaran on Twitter

Comments