The perception that female must be circumcised like male, as well as religious belief, social pressure, and encouragement from health workers are behind the rampant practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in Indonesia, a new research has revealed.

Conducted by Hivos Southeast Asia, an organization that focuses on global development, and Center for Gender and Sexuality Study at the University of Indonesia, the research found that among mothers who have had FGM procedure done to their daughters, 97.1 percent believe circumcision is a must for both male and female. About the same percentage of the respondents also said that they believe the practice has a strong religious justification, and that they did it because it is considered a cultural tradition practiced by most of the people they know.

The study, which was unveiled last week, found that up to 61 percent girls underwent female genital mutilation (FGM) before they turned one year old. It also identified a predominant perception that uncircumcised girls will be alienated because they are considered filthy and will grow up promiscuous and unwanted.

The report was based on in-depth interviews, literary reviews, focus group discussions and surveys conducted in Medan, North Sumatera; Sumenep, East Java; Ketapang, West Kalimantan; Bima, West Nusa Tenggara; Polewali Mandar, West Sulawesi; Gorontalo; and Ambon, Maluku. Held in January 2015 to April 2015, the study involves 700 respondents, half of them are mothers who had the FGM procedure done to their daughters and the remaining half are those who didn’t.

Insufficient Knowledge

The WHO (World Health Organization) determines female genital mutilation (known as “sunat perempuan” in Indonesia) as a very dangerous practice because it can cause severe bleeding, urinating problems, infections and many other complications, while giving no health benefits at all. The practice is considered a violation of human’s rights to girls and women.

However, the study recorded that up to 90 percent of Indonesian mothers believe that FGM will make their daughters healthier. A total of 84.6 percent also believe female genital mutilation can make their daughters’ vagina cleaner, 55.4 percent believe it will enhance their daughters’ fertility, and 54.6 percent believe it will control their daughters’ sexual drive.

In addition to false assumptions regarding the health impacts of FGM, the respondents practice FGM due to religious beliefs and social pressure. Up to 88 percent of the respondents believe that not circumcising their daughters would make them sinners, and as much as 36 percent believe that FGM will make it easier for their daughters to find a husband.

Based on their educational backgrounds, the highest number of mothers who circumcised their daughters are high school graduates at 32.3 percent, followed by elementary school graduates at 26.6 percent, and junior high school graduates at 23.7 percent. At least 9.4 percent of mothers who practice FGM have Bachelor’s degree.

Dangerous Procedure

Half of the mothers who have their daughters circumcised believe the procedure involves injuring the tip of clitoris, about 36.6 percent sees it as cutting a small part of clitoris, 9.1 percent believes it involves wiping the clitoris with antiseptic, and 1.1 percent sees FGM as the piercing or scraping of vagina.

The WHO categorizes FGM into four types, two of which are commonly practiced in Indonesia. One of the common practice in Indonesia is clitoridectomy, which is the partial or total removal of the clitoris or the fold skin surrounding the clitoris (the prepuce). In Indonesia, this can be found in Bima, West Nusa Tenggara, where the procedure involves cutting the tip of the clitoris that they called “isi noi.” In other areas in the country, such as Ambon, the same procedure entails a partial removal in the size of “biji padi” (a grain of rice).

The most common form of FGM in Indonesia, which was found in six out of seven areas surveyed, is what the WHO categorizes as type 4. It involves injuring the vagina until it bleeds a little, scraping the clitoris until it shows blood on the surface, or pinching the clit with small knife to extract the white “haram” part – a practice called “cubit kodo”.

Other than these two, female circumcision in Indonesia is merely a “symbolic” practice that does not involve cutting the vagina – practices like wiping the clitoris with cotton and dab the cotton with antiseptic to symbolize blood, a practice that is common in West Kalimantan and East Java. In Gorontalo the procedure involves touching the clitoris with a small knife; in some areas, there is even no touching of the genital involved.

More than half of the FGM procedures is conducted by dukun bayi (baby shaman) and a quarter is done by dukun sunat (circumcision shaman), while 17 percent of midwives and 0.9 percent of doctors conducted the procedure, the study shows.

The danger lies in the fact that the tools used for the procedures are not always hygiene.

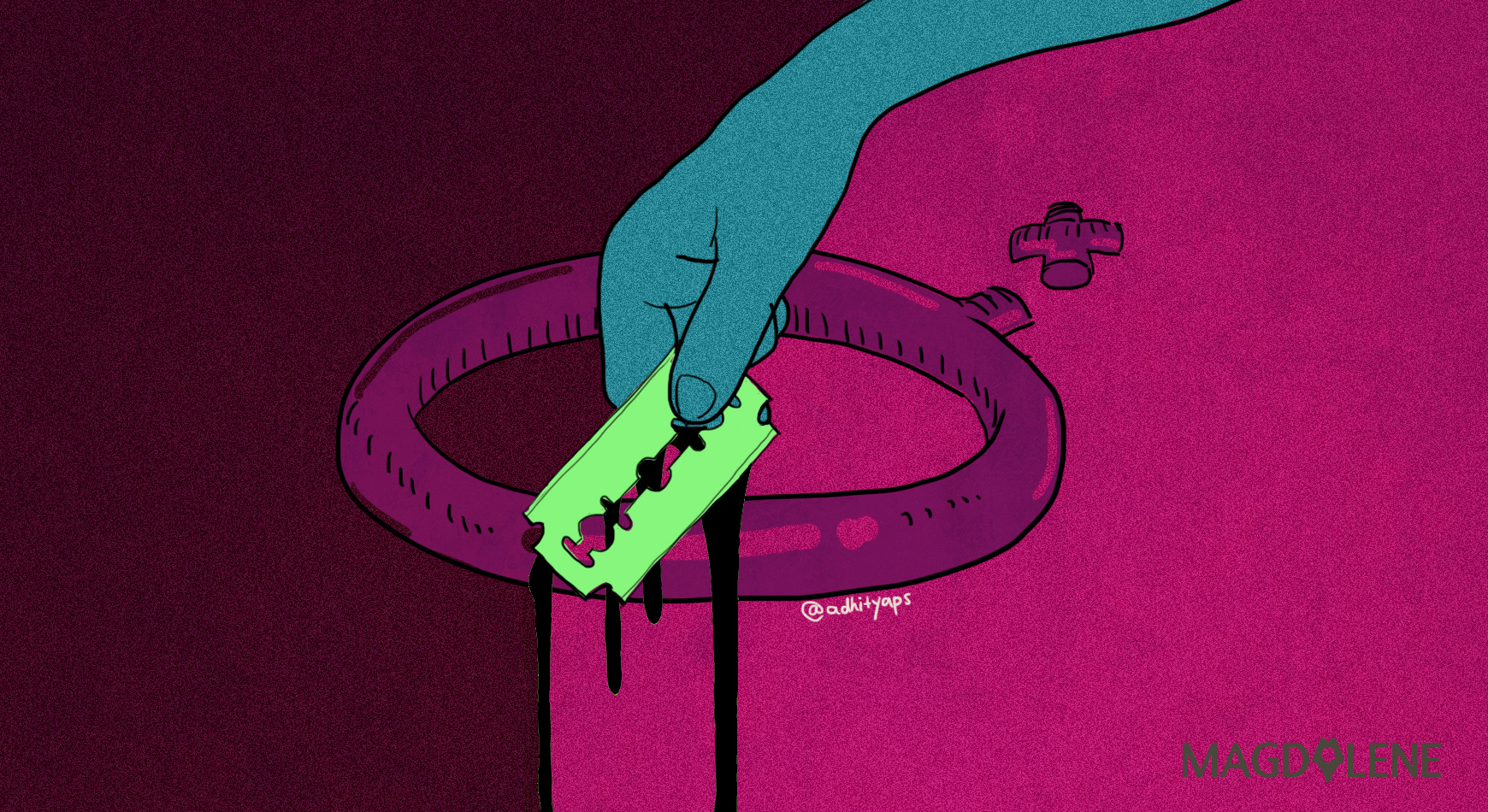

Dr. Johanna Debora Imelda, a member of the research team at the Center for Gender and Sexuality Study UI, listed some of the tools used in the procedures, from small knives, razor blades to eyebrow scissors.

“The small knife being used is usually considered sacred, so it is not washed for years, often ending up rusty,” she said during the launch of the report.

In the report a girl from Bima testified about her experience: “I was six years old and I felt so afraid that I cried. I didn’t have the courage to look at it. It bled for two days, so I was treated with traditional medicine. Then I was told to bathe in the sea. After the circumcision it felt painful when I peed.”

She recalled her friends’ experiences: “One of my friends was too afraid that she moved a lot during the process. She bled a lot like a woman in childbirth. Another one was so afraid to have it done after hearing of others’ experiences, so her parents persuaded her by buying her gifts so she would agree to the procedure,” the girl explained.

Social and Cultural

Johanna says the practice of FGM is deeply embedded in Indonesian culture, although female circumcision is not mentioned in the quran. The study found that society sees the practice as sacred and that it is the parents’ responsibility to have their daughters circumcised. Support and pressure from family, neighbors, religious figures and health practitioners contribute to a mother’s decision to circumcise their daughters.

Often women’s values lay on whether or not she is circumcised. There will be social sanctions to anyone who goes against the practice. The report describes how the different societies practice this. In Poliwali Mandar and Sumenep, for instance, women who are not circumcised are labeled promiscuous and believed to have high sexual drive. They also believe that women who are not circumcised run the risk of turning into sex workers. In Ambon, uncircumcised women are not allowed to enter the mosque, pray or read the Quran. In Bima no man would want to marry an uncircumcised woman.

Riri Khariroh, a commissioner at the National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan), said during the report launch that eliminating the practice of FGM in Indonesia will require redefining the term to shed its association with religion.

“We should change the term ‘sunat perempuan’ (female circumcision) because ‘sunat’ has a strong association and attachment to religiosity and is therefore difficult to eliminate. We should start using the term ‘pelukaan genitalia perempuan’ (female genital mutilation) instead,” she said.

This website encourages disabled women to reclaim their sexual rights.

Comments