I was disappointed, but had expected it. Pope Francis has made several statements on gay people since his election three years ago, but they made little impact among Indonesian Catholics.

Indonesian Catholics, who, like other Indonesians, put religion at the center of their social lives, share plenty of religion-related thoughts and information on social media every day. The latest issue is on which side the priest should face during Mass, along with problems of building churches in Java and parish politics. And plenty of group photos from weekend retreat and group luncheon.

But no discussion ensued when Pope Francis elaborated on his 2013’s “Who am I to judge?” comment early this year, and when he asked the Catholic church to be more accepting of divorced Catholics, gays and lesbians three months ago. One might anticipate a month of debates and opinions among Indonesian Catholics, but no. No one commented on the Pope’s statements, pro or con.

Indonesian Catholics are aware of homosexuality, as every class in any school and every choir group has someone taken as a closet gay. Like many other Indonesians, however, Catholics think that bisexuality is just a myth and they see Trans people as banci.

Catholic media and academics have a way to circumnavigate the Pope’s statements, praising his compassion and humanity while sticking to the bottom line: the Catholic Church does not accept anything besides the relationship and marriage between a man and a woman.

The hysteria surrounding Support Group and Resource Center on Sexuality Studies (SGRC) early this year was also noticed by Catholics, who also worried that there are “LGBTs” among them. Catholic psychologists and doctors agree that gay people should not be discriminated, and that they can be “cured” or contained. But beyond jokes where “LGBT!” was the punch line, I saw no further discussion online. Offline, everyone was more concerned about church politics and the economy.

Two months ago, the Association of Protestant Churches in Indonesia, the PGI, held a general staff meeting discussing the LGBT issue. The report states that LGBT is not an imported modern culture and the Bible does not condemn homosexuality. Rather, the bible condemns the perversion of sexuality such as rape and pedophilia. In conclusion, there is no “LGBT crisis”, and the churches and the government should accept LGBT people.

Surprisingly, this bold statement also did not make headlines. The topic was raised in my sister’s high school alumni WhatsApp group, but nobody replied. The Manado office of Independent Journalists Alliance (AJI) discussed the written statement in late June, and Protestant priests and scholars who appeared in the discussion agreed that the statement was necessary, as many churches were being intolerant on LGBT people and used the Bible to judged them.

When Indonesian school children learn about official religions in Indonesia and their governing bodies, they learn about Catholic Church and the KWI, and the Protestant churches and the PGI. In the 21st century, many Christian churches are not members of the PGI, and, instead, they belong to several minor associations or alliances. While the Catholic Church is vocal on social justice and Protestant churches show some support for women’s rights, these new churches are usually conservative on both social issues and sexuality.

Many Westerners did not notice the born-again Christianity phenomena until 2002, when journalists exposed “mega churches” to explain the worldview of George W. Bush. Evangelical Christianity rose in Indonesia in the 1990s and gained momentum after 9/11, at the same time when the Islamic piety became fashionable among the middle class. Both groups believed that 9/11 was the start of a religious war. A decade later the apocalyptic view had gone, but both devout Muslims and Christians are worried about the decadence of society, with gays and feminists everywhere.

In Southeast Asia evangelical Christians do not wish to convert Muslims (no Christian church here does) more than they want to evangelize Christians from other churches. Their service is highly energized with charismatic preachers, passionate worshippers, and spectacular shows of light and sound. Powerful businessmen often belong in such churches.

In Latin America the evangelists’ support for capitalism gives hope to people tired of the Catholic Church’s consolation for the poor, while in Asia their American origin is associated with wealth and success.

The direct clash between LGBT community and evangelical Christians has taken place in Singapore, as more Western corporations sponsor the Pink Dot SG, an annual LGBT gathering inside the Hong Lim Park. While there has never been any street protest and counter event against Pink Dot (which is impossible in Singapore), evangelical Christians have led the critics of Pink Dot and LGBT pride in the media, whether through letters to the editor or Facebook comments.

Last year IKEA Singapore was in the middle of the conflict after it promoted the magic show of Lawrence Khong, a homophobic pastor. This year a man was arrested after writing that he would “open fire” (one week before Orlando), and later claimed that he meant to debate foreign companies that sponsor Pink Dot. There is no indication that Bryan Lim’s homophobia is driven by religious conviction, but a good number of letters and comments criticizing Western sponsors of Pink Dot lamented the LGBT offensive against Christians in United States.

Some Christian churches in the West accept gay pastors (which means Protestant priests in English, not Catholic priests in Indonesian), and the majority of Protestant churches in Indonesia accept women as priests (evangelical ones included). While Catholic Church in Indonesia is more liberal than its counterparts in Asia and even Australia, in the 21st century it cautiously takes a more conservative approach, as more Catholics care less about social justice and feel jealous with the evangelists’ success.

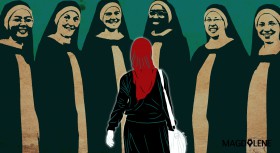

PGI’s council statement is an encouraging sign, but, again, each church and community has its own stance, and in Indonesia a Protestant church is closely tied to a particular culture. Like elsewhere in the world, it is not easy for an LGBT+ person (or even a heterosexual feminist) to be religious and at peace.

Read Mario’s take on the US gun culture and follow @mariorustan on Twitter.

Comments