A couple of years ago, when an organization campaigning against religious violence among youth published a survey that showed Indonesians were vulnerable to radicalism, its credibility was soon questioned by the usual lot of Islamist groups.

In various online platforms belonging to these groups, Lazuardi Birru was accused of many things, from being Islamophobic to trying to turn Indonesia into a western-style liberal haven.

They called the study a sham and said the organization was a proxy of the National Counterterrorism Agency, a government body much maligned by the hardliners.

“We get attacked all the time, but, thankfully, so far the attacks had not been physical or direct,” the organization’s head Dhyah Madya told Magdalene in an interview.

In this most populous Muslim country, where many prefer to avoid critical discussions on religion, conversations that verge on self-criticism are fostered by a select bunch uninhibited by the typical charges of “infidels” or “westernized liberals” often hurled at them.

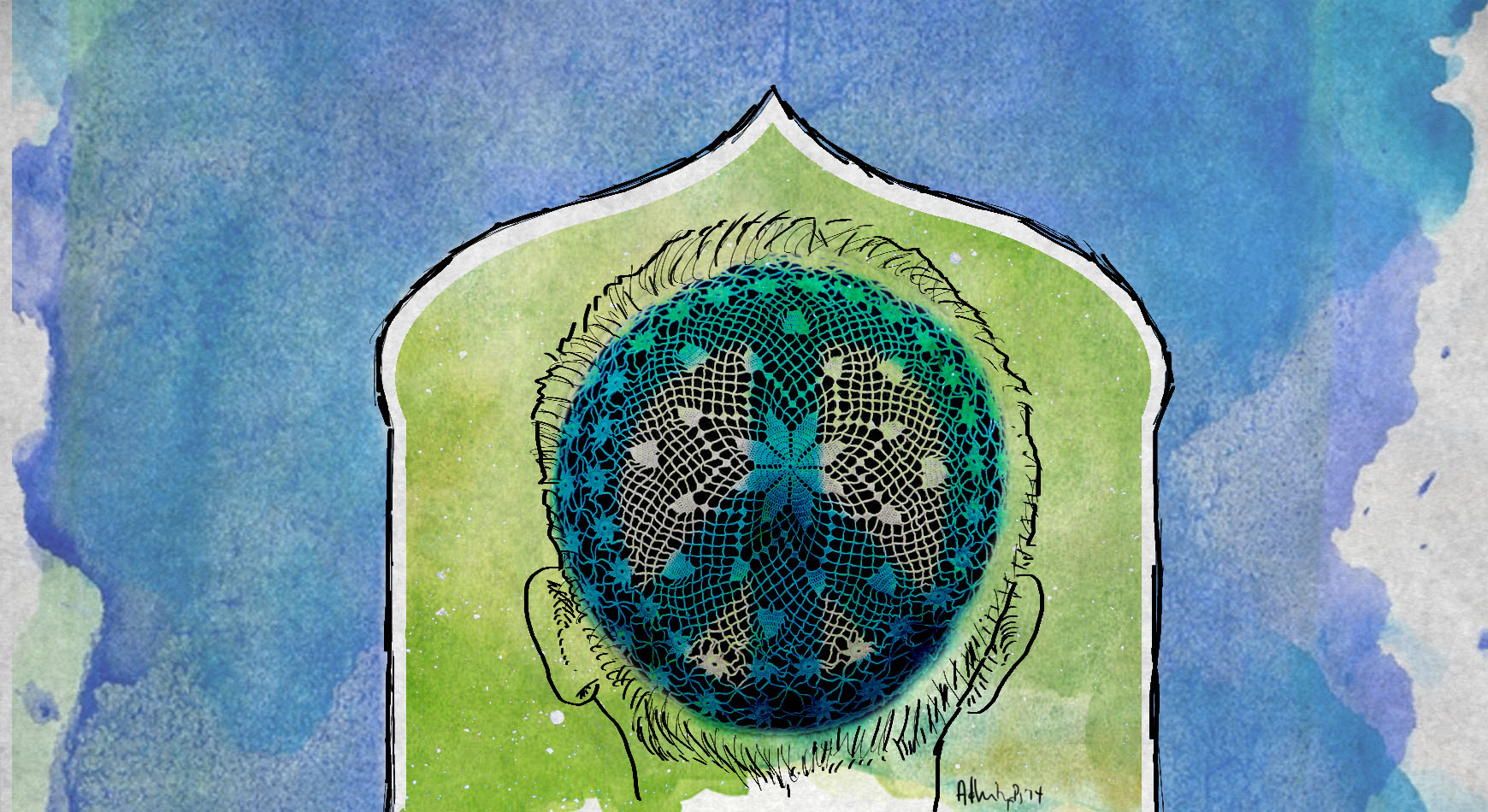

Lazuardi Birru, whose name means blue horizon, is one of them. It was founded in 2009 by a group of lawyers, including the hijab-wearing Dhyah, a former human rights lawyer turned public notary.

Initially, it aimed at addressing violence among high school students in the often fatal tradition of inter-school brawls or tawuran. Around the time, Indonesia had seen a spate of suicide bombings in the last eight years, and as the police uncovered the network of Muslim militants behind these attacks, it became clear that most of the perpetrators were young men, as young as 16.

“Some of the terror attacks in Indonesia involved relatively young men, most under 25 years old who wanted to be martyrs,” said Dhyah.

According to the group’s Index of Social Religious Radicalism published in 2011, a total of 1.3 percent of Indonesia’s 245 million population have perpetrated violence.

It also found that men under 25 living in the rural areas are vulnerable to radicalism, because of their understanding of jihad as a violence-based struggle to achieve an Islamic country. Their beliefs are based on a narrow interpretation of Quran, a “scriptualistic” perspective, Dhyah said. But the radicals are not necessarily who Lazuardi aim to reach out these days.

“There is a contestation between the pro-violence and the pro-peace groups, but there's a large number of youth in the middle of this tussle,” she said.

“Lazuardi Birru now focuses on reaching out to these so-called neutral kids to prevent them from being pulled to the radical side,” she said.

The group does this through a multi-approach campaign to educate the youth through discussions, books and videos.

Last year, for example, it conducted a youth leadership forum involving a few hundreds selected students from various high schools in Indonesia. Each school was represented by the president of the student body, the head of the Islamic Club, and the editor of the students’ publication. They are expected to pass the anti-violence message back to their peers at home.

Muhammad Adri Waskito, 19, a psychology student at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, attended the three-day event in his last year in high school in 2013.

“We were given training on leadership and talks on religious issues, like a kind of comparative overview of other religions too – basically to stay away from radical views,” he told Magdalene over the phone from Yogyakarta.

A big part of Lazuardi’s message of peace is a reminder of Indonesia’s diversity.

“The talk on nationhood made me appreciate how big and diverse a country Indonesia is,” said Adri.

Asked if he thought that Indonesia should be an Islamic country, he said, ”I don’t think so. Our country is built with Pancasila (the five principles) as our ideology.”

Another survey conducted by the Institute for Islam and Peace Studies (LaKIP), however, have shown that many students in the Greater Jakarta area no longer accept the state philosophy, and want Indonesia to become an Islamic state.

The same 2011 study, which involved 590 Islamic study teachers and 993 middle and high schools students, found other indications of increasing religious intolerance, including the refusal of construction of a church in their neighborhoods and approval of some religious radical figures and organizations.

These sentiments are equally shared by both students and teachers, including an overwhelming 65 percent who thought the imposition of the sharia or Islamic Law in Indonesia would solve the country’s problems.

Acknowledging its limitation as a small organization with restricted funding, Lazuardi spreads its message through books and online forums.

It has published a couple of graphic novels telling the stories of Bali bombing convict Ali Imron, who confessed and collaborated with the police against the other three perpetrators who had since been executed, and Malaysian-born Nasir Abbas, a convicted militant leader who became a vocal campaigner against religious violence.

Another book explores Indonesia’s diversity and its rich history that predates the Islamic period, and yet another is a manual for teenagers that highlights all kinds of violence, from tawuran to terrorism.

They publish a couple of books on Islamic teaching, one for younger audience and the other for religious teachers, that address some contentious verses that are often interpreted to support violence. These include the relationship between Muslims and non-believers and how to recognize and steer clear from pro-violence propaganda. The electronic versions of the books are available for free downloads.

They post interviews and animated films on YouTube, and give workshops to Islamic teachers and ulemas on peaceful interpretation of Islam. They use trainers and Islamic teachers who communicate often complicated religious teaching in simple language and with contemporary contexts.

“What we do is give the students and teachers a different understanding of Islamic teaching than what they have always known. Like, instead of seeing jihad as a holy war to create an Islamic country, we can focus on how we internalize the religious values in our lives,” said Dhyah.

She said Lazuardi’s studies had been used as baselines for some government policies, including a Presidential Instruction issued last year to manage conflicts and another policy being drafted on deradicalization efforts.

Understandably, not all its surveys were published. Magdalene understands one of their studies shows that an increasing number of Islamic institutions, including mosques, are vulnerable to radicalization. This survey was never made public due to the sensitive nature of its content that could jeopardize its good relations with the government.

Dhyah would not comment on this, adding Lazuardi works with everyone, whether the government or private institutions.

Meanwhile, they are faced with the challenge of keeping the people they’ve connected with – including 1,500 students who took part in their trainings, and 1.8 million of followers on Facebook and thousands others on their website and Twitter account – engaged so the message of peace can stay alive.

“Our real target audience are the boys who live in Islamic boarding schools in rural areas, but these kids’ schedules are either too full already or they don’t have much access to the Internet. This is our challenge ahead, to reach out to them,” she said.

After all, the Internet has been an effective breeding ground for militants, a virtual field where the battle of ideologies is brewing.

Follow Devi Asmarani on Twitter

All photos courtesy of Lazuardi Biru

Comments