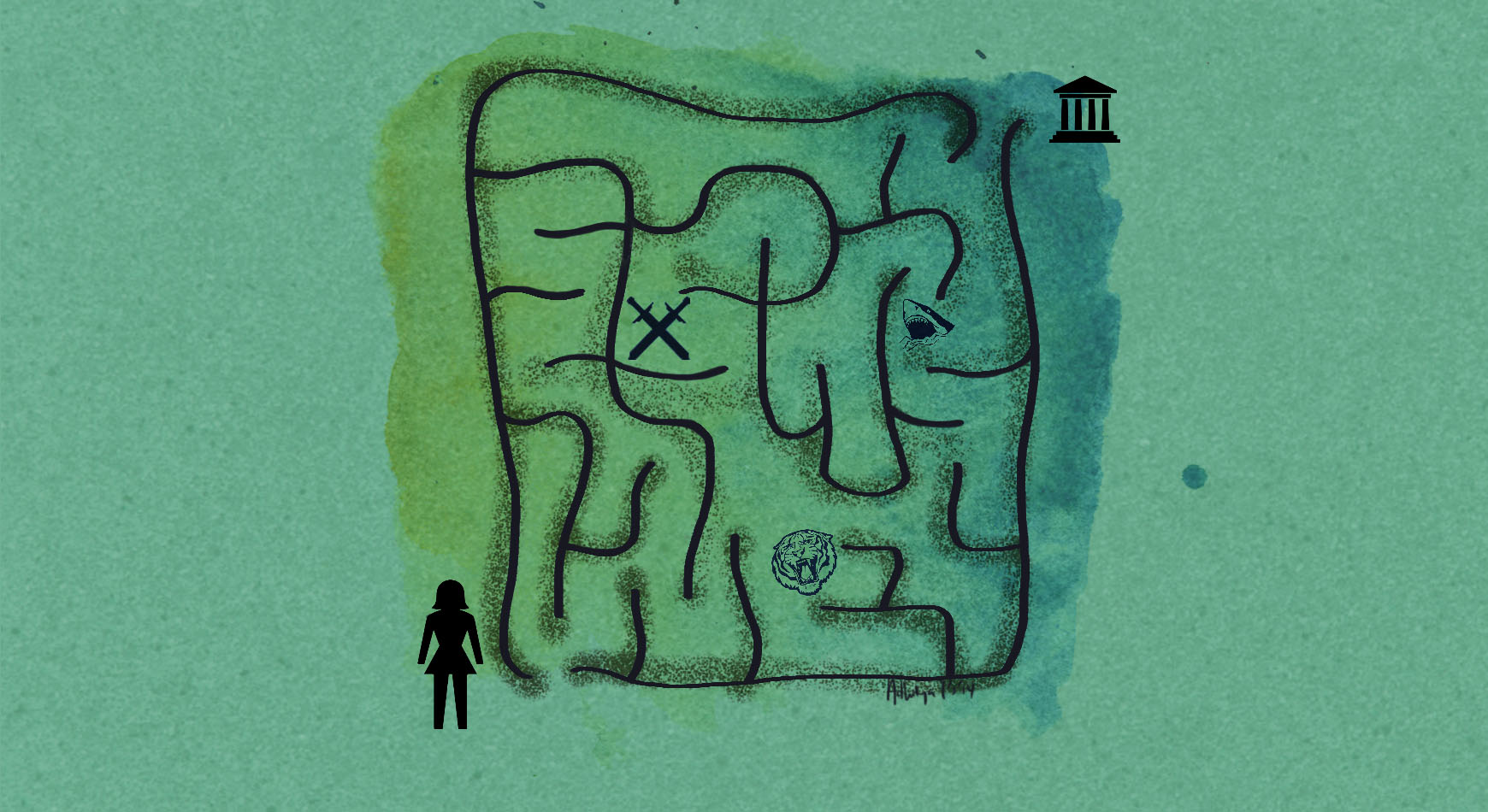

One late afternoon in Jakarta, Marcella, sitting calmly in a café, asked if she was allowed to smoke. As she lit up a cigarette, the 31-year-old started recounting a harrowing experience she went through one year ago in December 2016.

She had just left her workplace and was struggling to find transportation to go and meet her friend during that rainy night. Suddenly, a man on a motorcycle offered her a ride. Using motorcycle taxis, locally called ‘ojek’, was far from uncommon in the Indonesian capital, where heavy traffic is a problem.

“I couldn’t find an ojek ride with the smartphone app. And I had no suspicious thoughts. Until that moment I was quite trusting toward strangers,” she said.

Marcella thanked the man for the offer, and told him where she wanted to go. Riding pillion on his motorcycle, she kept busy with her mobile phone, texting and choosing a song to listen to. At one point, the driver stopped at a quiet residential area, where he said he needed to find gas for his motorcycle.

“He asked me to wait there, and because there were houses and some people, I said ok. I think I waited for 10-15 minutes until he came back,” she continued.

She brushed off her worries when the man came back empty-handed, saying he could not find any small shops that sell petrol. But her suspicion reached a peak when they started heading for a deserted area without any lighting, save from the motorcycle’s headlights.

Marcella panicked when she saw the silhouette of another man waiting for them. When the driver stopped, she quickly jumped off and tried to run away. But they managed to subdue her, then took her to a small dilapidated hut where they raped her.

“They threatened to kill me if I screamed. I think it was instinct, I just kept quiet while one of them told me there was another girl who was killed at the same place,” she recalled. “At that time, I really thought they were going to kill me.”

The two men took her ATM cards and demanded their PIN codes, as well as her engagement ring. After three hours, they dropped her off on the street – and called a taxi for her. Marcella reported the rape to the police on the same night on Dec 8.

Marcella’s traumatic experience was one of the 1,036 cases of rape reported in Indonesia in 2016, according to the Annual Report by the Indonesia’s National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan). The data was released in March 2017. The government agency, which focuses on advocating for women’s rights, compiles data on violence against women every year together with partner institutions.

In its 2017 report, which includes figures from January to December 2016, Komnas Perempuan reports a total of 5,785 cases of sexual assaults in the country, including rape and harassment. Out of that same total, 3,495 crimes were committed by someone whom the victims knew personally.

Mariana Amiruddin, a commissioner of Komnas Perempuan, says that women are more vulnerable to gender-based violence in a patriarchal society such as in Indonesia, where men dominate nearly all aspects of life and women are expected to be subservient.

The condition is exacerbated by the lack of laws with a gender perspective.

“We don’t have a law that is sided with women, that deals specifically with gender issues,” she said.

In any case of sexual violence, for instance, offenders can be charged under Chapter 14 of the Criminal Law Procedures Code (KUHAP), which is about crimes against morality. But Mariana argues that without a law made specifically for women, authorities would treat the case as a crime that can happen to anyone.

“But rape or sexual violence are different because women are more vulnerable, and the law must also protect the victims and prevent future occurrences. Now (the law) is seen only as an instrument to sentence or punish someone,” she explained.

Indonesia’s House of Representatives is still discussing a bill on the elimination of sexual-based violence. First introduced in 2016, it is still waiting to be passed into law a year later. Mariana said that the law would be a lex specialis, or a specific law governing a certain matter. She hopes that the bill will become law within the next year.

As ASEAN’s most populous member state with 260 million people, Indonesia does not fare better than the other nine countries when it comes to gender-based violence, she adds. In particular, she notes a lack of political will to solve such issues unless they are seen to bring political benefits to the incumbent government.

“It’s complex and complicated, but at least in our community, there are people who understand and fight to eliminate the problem,” Amirrudin pointed out.

Different country, similar problems

Unlike Indonesia, the Philippines has several laws that deal with violence against women. Republic Act 9262 or "The Anti-violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004", which defines violence against women as any act that can result in physical, sexual or psychological harm on a woman or her children. A new Anti-Rape Law, or Republic Act 8353, was passed in 1997.

But the passage and existence of laws alone have not solved gender-based violence in the country of 105 million people. According to the Philippines’ Commission on Women, there were 1,034 rape cases reported under the RA 8353 and 15,749 cases of violence reported under the RA 9262 from January to June 2017.

Emmi de Jesus, a member of the House of Representatives with the Gabriela Women’s Party, explains that the Philippines, despite its track record as doing better on women’s status and opportunities, still has a long way to go to eliminate all forms of violence against women.

“Aside from weaknesses and loopholes in the current legislation, implementation remains a huge stumbling block in the realization and promotion of women’s rights,” she said.

Some of the challenges in implementation include the need to inculcate among government officials gender sensitivity and an awareness of the need to protect victims. Meanwhile, there have been cases where victims are asked to settle dispute amicably to avoid lengthy legal processes, similar to what also happens in Indonesia.

Clara Rita Padilla, executive director of the non-government group EngenderRights, says rape especially is still too prevalent in a society that remains patriarchal. “It will lead to violent acts. Women and girls can’t be just another rape statistic,” she said in an email interview.

She adds that although there are laws, prosecutors and judges sometimes dismiss cases filed by victims of gender-based violence, denying women and girls justice. “Providing training for the pillars of the criminal justice system is important. All these efforts need the necessary funding support to end this culture of machismo and impunity of rapists to make our country safe,” said Padilla.

It is not surprising that women, such as journalist Mariejo Ramos, feel unsafe walking alone in the streets of the Philippine capital, Manila.

”I still fear being catcalled, molested, and robbed,” she pointed out.

How far can a regional body go?

It has been more than seven years since ASEAN established the ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children (ACWC) at its 16th ASEAN Summit in 2010. Its purpose is to develop policies and programs to promote the human rights and fundamental freedoms of women and children in the ASEAN region.

Eliminating violence against women is listed as a priority issue in ACWC’s five-year work plan from 2010 to 2015. “And one of our mandates is to implement the CEDAW (Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women),” said Lily Purba, a gender consultant and the outgoing Indonesian representative to ACWC.

Purba, who ended her term as ACWC chairwoman in October, says that all ASEAN countries have ratified CEDAW and are thus, parties to it. The Philippines was the first member state to ratify the convention in August 1981.

Through the ACWC, ASEAN member states adopted the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women and the Elimination of Violence against Children in ASEAN in 2013. Although it is not legally binding, Purba says the declaration makes several recommendations on issues such as gender mainstreaming and violence against women.

“We have a concrete action plan on what to do from 2015 to 2020. And we have started on data collection and analysis,” she explained. The commission has also published several guide books on how to deal with victims of sexual violence and rape survivors, Purba adds.

But for organizations such as Gabriela in the Philippines, ASEAN is merely paying lip service to the issue of violence against women through the 2013 declaration. “The fact that it is not legally binding shows that it is merely to accommodate civil society’s pressure to address women’s issues in ASEAN,” said de Jesus, adding that the document does not say much about each member states’ willingness to address the issue.

Moreover, as stated in its terms of reference, the commission makes decisions based on consultation and consensus, in accordance with the ASEAN Charter. That means the regional body also uses the policy of non-interference, which is often seen as hindering its effectiveness. Purba concedes that some issues remain a challenge because of the limits on what a regional body can do, and the fact that it cannot interfere with the states’ internal matters or dictate its national laws.

“There are member states that do not fully accede to CEDAW because of culture and practice in the country. For example in Indonesia, FGM (female genital mutilation) is still common although local health centers are forbidden from performing it. Or in another case, child marriage is allowed because the girls are old enough based on religion (in majority-Muslim Indonesia),” she explained.

Education to change mindsets

De Jesus does not believe that ASEAN needs a legally binding regional instrument to address gender-based violence. Instead, she stressed, member countries should put more emphasis on education and campaigns to uphold women’s rights, and to change societal mindsets about women and gender. “And bring to the fore the various forms of violence against women,” she added.

As for Gabriela Women’s Party, it holds regular discussions on gender issues in the Philippines through their Grassroots Women’s Advocacy Program and Action (GWAPA) school. It also has courses on violence against women and basic gender rights.

Gabriela also advocates for amendments in existing laws on gender-based violence.

Meanwhile, Anita Dhewy, editor-in-chief of Jurnal Perempuan (Women’s Journal) in Indonesia, says that although the NGO does not work with a regional body such as ASEAN, it is actively campaigning for the passage into law of the bill on the elimination of sexual violence against women. “It is the duty of the state to protect its citizens,” she pointed out.

Mariana says she does not see the direct influence of ACWC’s work in the archipelago, but still thinks it is important to bring up the issue of violence against women in a regional venue like ASEAN. Such a space might help create political will for a member country to act on a pressing matter, she explains.

“When (our leaders) meet with another country, for example, they might ask why Indonesia does not have a gender-responsive law yet. Hopefully, that will somehow create an impact,” she said.

Despite the challenges to eliminating a problem that women are vulnerable to – more than 50 percent of Southeast Asia’s 630 million people are women – the ACWC’s establishment itself was seen as a step in the right direction for ASEAN. Purba asserts that its programs are aligned with CEDAW, and that the ACWC actively cooperates with the governments of each member state in ASEAN.

Assured Purba: “It’s slow but there is progress.”

This story is produced under the SEAPA 2017 Regional Reporting Fellowship. It has been slightly edited from the original version that appeared on Reporting ASEAN.

Comments