Last year, a proposed bylaw to make virginity test compulsory to secondary school students in Jember District, East Java, was quickly shot down after stirring up nationwide controversies. Ludicrous as it seemed, however, it wasn’t the first time such an idea was raised.

District heads, mayors, politicians and local ulemas across Java and Sumatra – unsurprisingly, all men – have also championed virginity test for similar purposes in recent years, though none have succeeded in pushing for its approval. And it probably won’t be long before the idea gets resurrected by another publicly elected officeholder, eager to proof that he is a trusted moral guardian of his constituents.

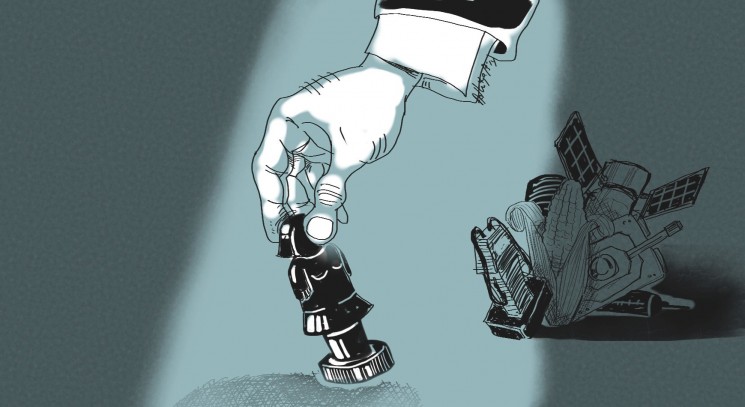

Sexist and invasive local legislations, not unlike the proposed virginity test, have increasingly become a hard-hitting reality in Indonesia. Eighteen years after the momentous Reformasi that altered the country’s political landscape, ushering democracy and decentralizing powers to the region, Indonesia is facing a serious constitutional challenge posed by local legislations that regulate morality based on religious values.

In 2015, the National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) found 389 discriminative regulations issued across Indonesia in the past five years, including four at the national level. The remaining 385 were bylaws issued by provincial, district and municipal administrations – 31 of them came out in the last year alone. Of these bylaws, 82 percent directly discriminates against women. The rest targets minority groups based on their faith, gender expression and sexual orientation.

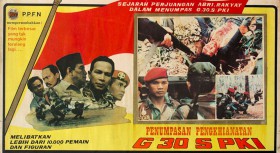

Known for its strict interpretation of Islam, Aceh is a “poster province” of this phenomenon. A 60-year-old Christian woman was caned in public last week for selling alcohol, which is illegal, the first time ever a non-Muslim was punished under Sharia law in the province. This was made possible by the new Islamic criminal code called Qanun Jinayat, which came into effect in the province late last year to replace a more limited collection of Islamic bylaws. Among offences punishable by 100 lashes of the cane or 100 months in prison are sex out of wedlock and same-sex sexual acts. Others offences include consuming or selling alcohol, gambling and mixing between unmarried opposite sex.

The situation warrants civil society organizations to declare “red alert”, calling for massive political and legal intervention. They point at what’s happening in Aceh as an example of what the rest of Indonesia could become.

“This is regional autonomy that has gone way too far,” Riri Khariroh, Commissioner at Komnas Perempuan in charge of constitutional issues, tells Magdalene in an interview.

Religion and Politics

According to Komnas Perempuan, a little over a third of the regulations criminalize women through “morality” bylaws, which often lead to arrests of women for suspicion of prostitution. A quarter other bylaws regulate women’s body by requiring them to wear Islamic dresses, including headscarf and – at least in one district in Aceh – a ban on wearing pants. Another district in Aceh bans women from straddling when riding pillions on a motorcycle.

There are also many bylaws that restrict women’s movements through curfews or requirements that they be accompanied by a male blood relation after certain hour. Some bylaws deal with female workers, for example, by requiring women wanting to become migrant workers to get spousal permission. Increasingly, there are bylaws that impose strict observance of religious rituals, such as the requirement to read the Quran fluently for civil servants seeking a promotion, or for couples planning to get married. And, lastly, there are bylaws that infringe on religious freedom, such as bans on the Islamic sects Ahmadiyya and Shia.

"Aceh is a red zone for us, because we are worried about its trendsetting effect."

The rapid growth of these bylaws reflects growing conservatism in Indonesia, where political Islam has grown stronger particularly at the regional level in the last two decades. The two provinces with the highest number of discriminative bylaws are West Java and Aceh. With 56 discriminative bylaws, Aceh was granted the rights to impose its version of Islamic law after a peace agreement between Jakarta and separatist rebels in the former restive province over a decade ago. Similarly, nearly a quarter of the discriminative bylaws were issued in districts and townships throughout West Java, which was once a hotbed of Islamic secessionist movement the Darul Islam (DI).

“West Java’s political landscape has been dominated by the Prosperous and Justice Party,” says Daden Sukendar of the Institute for Social and Religious Studies (Lensa), a West Java-based civil society organization, on the Muslim-based political party known as PKS.

Lensa has been focusing on advocacy work in Sukabumi and Tasikmalaya to lobby for the revision of discriminative laws issued there, particularly on female migrant labor.

“The bylaws rule on the recruitment of female migrant labors, but they provide very little protection for the women. It’s almost akin to legitimizing human trafficking,” Daden tells Magdalene.

Other reputedly religious provinces with a high number of discriminative bylaws, such as West Sumatra and South Sulawesi, have also been historically linked to the separatist group DI in the 50s and 60s. But the trend goes beyond ideologies.

“Some of these bylaws and policies are ideologically driven, but many are just pragmatic politics,” Riri says.

Regional administrations began issuing bylaws after Indonesia implemented regional autonomy in 2004.

“Regional autonomy encourages the regions to showcase their ‘unique identity’, and, for some reason, it is always associated with their religious credential,” says Riri.

Districts and municipalities soon adopted Islamic-sounding slogans like “Gerbang Salam” or “Bangkalan Islam” to distinguish themselves, and later they began to issue local regulations and bylaws inspired by religious teachings.

According to 2004 Law on Regional Autonomy, however, matters related to religion – as well as defense, finance and foreign policy – are under the authority of the central government, which means regional administrations cannot legislate religious affairs. But the implementation of the 2004 law has been less than consistent: currently regional governments has the power to issue permits on the construction of new houses of worship, which has made it nearly impossible to build new churches in some areas.

Politics play a big role in the emergence of the discriminative legislations. A lot of the regulations and bylaws were issued around the time of major political events, particularly the direct elections of local administration leaders. In some districts, bans on the Ahmadis and Shiites were issued suspiciously close to reelection time. In other areas, mayors or district heads that have been linked to corruption cases issued bylaws that require men to conduct prayers in congregation (as opposed to individually), women to cover up, and school children to take extra Quran lessons at Madrasah in the afternoon, in addition to their schooling.

“These regulations were issued not just by leaders affiliated with Islamic parties, but also those from nationalist parties,” says Riri. “It’s an easy way to polish an incumbent’s image by boosting his Islamic credential for vote-getting purposes, showing that he is virtuous, and possibly diverting public attention from corruption and other more pressing issues.”

But most of all, the bylaws reflect a generally poor understanding of the 1945 Constitution among the political elites in the regions, as well as their poor legislative skills. In their eagerness to produce the bylaws, some districts merely “copy pasted” those issued by other administrations (so mindlessly done, it appears, that some bylaws still contained the name or specifics of the original districts/municipalities from which they were lifted). The enthusiasism for replication even led to some districts to mull adopting caning punishment like Aceh.

"Aceh is a red zone for us, because we are worried about its trendsetting effect," says Riri.

Revoking Discriminative Bylaws

Finding the basis to rescind the discriminative bylaws is not difficult at all. Asides from violating the 2004 Regional Autonomy (which bans regional governments from regulating religious affairs), the discriminative nature of the bylaws prove them unconstitutional.

Following the LGBT scare early this year, for example, the District Office of Sharia in Bireun, Aceh, issued a circular that bans beauty salons from employing homosexual men and women and transgender people. The move would have a devastating affect on the local transgender community, most of whose members work in beauty salons, because of their lack of formal education as well as limited access to other fields of work. This type of gender-based discrimination is unconstitutional and could result in the impoverishment of this vulnerable community.

For the most part, the government fears that revoking religious-related bylaws would stir up "commotion" - in other words, they're too politically sensitive to bother with.

In the past only the President could revoke bylaws, but the issuance of the Law No. 23/2014 on Regional Government has simplified the process to review and revoke regional bylaws. The law gives the authority to revoke a bylaw to the next higher level of government. Now a district or municipal bylaw can be revoked by the governor, and a provincial bylaw can be revoked by the Home Affairs Minister.

Komnas Perempuan has worked with the Home Affairs Ministry for the past seven years to repeal the discriminative bylaws on the ground that they’re unconstitutional. But to this day only one bylaw has been revoked out of the 389 (the Tasikmalaya district bylaw on the punishment of forced marriage to unmarried couples found being alone late at night). The Ministry has reviewed 23 other bylaws requested the respective governments for “clarification”, but little follow-up has been done since.

Last year, the Jokowi administration, just freshly inaugurated, vowed to review some 3,000 “problematic bylaws”, but it turned out that more of them were related to locally imposed taxes and duties. For the most part, the government fears that revoking religious-related bylaws would stir up "commotion" – in other words, they're too politically sensitive to bother with. Even activists who do advocacy work on the field admit that it’s hard to criticize discriminative bylaws, saying it is the fastest way to gain the label “anti-Islam” or “anti-Sharia”

Daden of Lensa in Sukabumi says he has been able to do advocacy work on this issue because of his leadership role in the local moderate Islamic organizations. But even so, having a critical view on discriminative bylaws have made him stand out in the largely conservative local political scene as “that pluralism guy”, a slightly pejorative word associated with the liberal brand of Islam.

At the core of the matter is the poor grasp of what discriminative policies constitute, even among the highest level of government officials in Jakarta. In its statement last year, Komnas Perempuan said that many decision makers in the government do not fully comprehend the concept that every citizen is constitutionally guaranteed to equal rights. This is often reflected in the way officials perceive sexual violence not as a crime issue but morality issue (which consequently puts the burden of blame on women), and their poor understanding of the concept of separation between the state and religion.

Another major factor behind these problematic bylaws is that they were issued without prior consultation with the constituents.

“Do all women really agree to wear a hijab? Are all men able to conduct prayers in congregation every time? Can parents really afford to send their kids to madrasah for extra Quran lesson? These were never a part of the public discourse before the issuance of these bylaws,” says Riri.

Adding to this, public involvement in politics is pretty low in general, outside of election season.

Says Daden: “For the most part, people don’t really think about how their lives are impacted by the bylaws, as long as the prices of basic food remain stable.”

There is hope: recently the government has signaled its intention to engage Komnas Perempuan to address this issue. It remains to be seen, however, whether it would accelerate the efforts to review the bylaws.

Komnas Perempuan is also calling for the Supreme Court to make its process of reviewing regional bylaws more transparent, and it continues to conduct constitutional workshop for decision makers in the local and central government to prevent new discriminative bylaws from being issued. At the same time it engages “local reformists” in the region like Daden to advocate the issue at the local level.

“Progress is slow – sometimes we wonder whether we’ve actually accomplished anything at all, but all we can do is continue doing what we do,” Riri adds.

Read Devi’s take on heterosexual privilege and follow @dasmaran on Twitter.

Comments