My sister often tells me what is going on in the WhatsApp chat group of her friends from high school, which provides a glimpse of the lives of middle class Chinese-Indonesians for both of us (the kind of stories you won’t see in mainstream media or social media).

Recently we were horrified to read a live update – a child was kicked out of the house by his father and the mother was reporting the incident live to the group.

Imagine knowing an incident developing before your eyes, also witnessed by dozens, and knowing you that you could do nothing. According to the mother, the boy was fighting with his sibling, throwing a punch at her, causing his enraged father to banish him outdoor. Not just to the front yard, but beyond the fence. Into the dark neighborhood street. He was wailing outside the gate, while his mother tried to sneak past her own husband to provide comfort for her son, under the cover of darkness, behind the family car.

Older Indonesians are pretty familiar with the image of “being locked in the bathroom” as a form of punishment. I am not sure if my mother experienced it, although she said she feared her father’s leather belt.

That was back in 1960s. Locked out of the house is still a trope in Asian cartoons. Nobita of Doraemon has been locked in the shed for bad test result (in 1970s), and Korea’s Jadoo is also thrown out of the house for her rebellious behavior (in 2000s). A friend who drew comic series for my local church used the “standing in the front yard” gag after a boy exposed his mother’s double standard.

Two days later I asked my sister how the story ended. That was that, she said. The boy had returned to school and his mother had moved to another topic. Meanwhile, the group members mostly expressed horrified reaction to the story, while a minority remarked that child discipline is necessary for the sake of his or her future.

The latter is still a popular opinion – more than it should be – in Indonesia. I was stunned to see two friends I know well sharing the same post on Facebook. A Central Javanese motivational guru laments the state of modern schools, where students are no longer submissive to their teachers.

He said that in the good old days, students literally treated the (male) teacher as their master, but now children disrespect teachers because teachers are not allowed to hit students anymore in the name of human rights.

It did not seem to be a controversial post – as the comments responding to the original post approved the message (and no one challenged my friends, including me). By sharing this post without adding their own commentaries, it seems that my friends agree with his message. Two of them are women in the 20s and one of them is a teacher. The major premise of the post is that the archaic education system is better, because obedient students make obedient citizens. The minor premise is corporal punishment in school is a good idea.

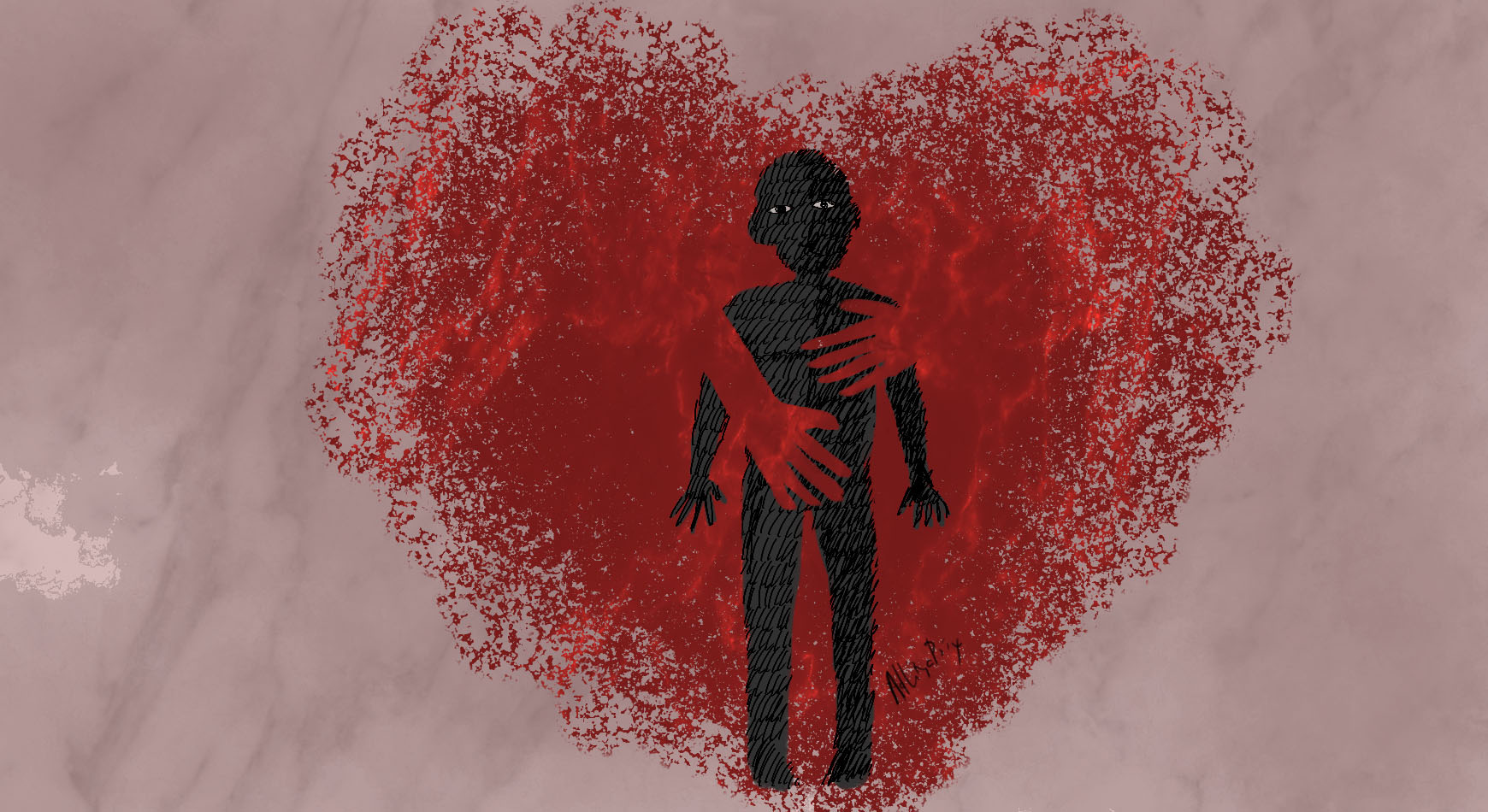

It scares me to think how many of my friends had been physically and mentally abused by their parents.

What I know is that in this decade, there are people who still believe that the practice is acceptable. A friend recommending a counselling program for husbands said, “It’s stinging like a loving father’s slap.” Another said that when she went into a yelling match with her sister, their mother told them to get the kitchen knives and kill each other. In school a friend told me about his luck when his father’s camera fell into a full hamper, not because it’s expensive, but because otherwise he would have been beaten.

On to another Facebook anecdote. There was a post circulating, written by another motivational guru specializing in “hypnotic therapy”, who asked her students to write their wishes for their parents. The writings are heartbreaking: the children asking their parents to stop cursing them and stop hitting them. Terrible deeds had been done and if the parents paid the therapist to discover what’s “wrong” with their children, she had found out what happened.

Child abuse used to be universally accepted. A century ago, English-speaking people still subscribed to the view “spare the rod and spoil the child” and there are similar expressions in other languages. Many cultures endorsed child abuse to prepare boys for the military and the girls for the village politics; and to prepare the children to obey the authority.

But instead of fostering better behavior, child abuse just perpetuates a cycle of violence – people who grew up being abused do the same thing to their children.So why is child abuse still practiced? It is easy to lose patience with a child or a teenager, but I fail to see how someone could have the heart to hurt a child, even verbally.

My Chinese History lecturer – who witnessed a mother berating her son for making a westerner see her punishing him and thus making her losing face – said that “leave the house” punishment is favoured by Chinese parents as exclusion from society, represented by the home, is the nightmare scenario in Chinese psyche. Throughout world history, a rebellious child could be deadly for the whole family, as the authority would punish the whole village for a person’s transgression.

Of course that is the past and we are in Indonesia. But I have heard more than once that Chinese-Indonesians, along with Singaporeans and Chinese-Malaysians, said that Singapore is a developed country because the people are disciplined and Indonesia and Malaysia are not because the people are unruly.

This is an absurd simplification, and I still fail to see how exposing your children to harm make them respect you more, let alone turn them into a better person. Why not talk to them instead about what is good and what is bad? Or can’t they make the distinction?

Read Mario’s take on evil men and the children who frighten them.

Comments