I didn’t write anything special to commemorate Chinese New Year 2018, something my old self would find outrageous. Years after years, I would write something for The Jakarta Post every February, on the visibility and representation of Chinese-Indonesians. In some years, February was the only time when Chinese-Indonesians were discussed on media, when academics would write op-eds on race relations in newspapers, and Chinese-Indonesian celebrities got interviewed, before it was back to being underreported again - and to staying away from the limelight - for the rest of the year.

Ironically, Chinese New Year does not have any special meaning to me. My family never celebrates it because both my parents prefer Christian and Dutch cultures, and no aspect of Chinese New Year celebration catches my attention. For millions of Chinese-Indonesians, however, it is such a blessing that Chinese New Year can be celebrated in peace, without any legal or security threat. Before 1998, the government and the military would make periodical reminder, without reason given, that it is illegal to perform a barongsai (lion) dance, to play Chinese songs in public, and to show Chinese ornaments in shopping centers.

I never expected that the latest challenge to Chinese New Year celebration would come from China. First, The Guardian published an article arguing that Chinese New Year celebration in the United Kingdom is outdated for Chinese visitors, and it is wise for Britain to catch up with modern China. One and half week later, ABC News featured a similar article, saying that Australia gets Chinese New Year “celebration” wrong, prompting me to file a complaint with the ABC.

Both articles have similar structure and messages, as if following a single guideline. Both writers are senior journalists based in Beijing, who correctly said that Chinese diaspora in the UK and Australia mainly came from Canton/Guangdong province and define what the world considers as Chinese culture – Chinatown, sweet & sour chicken and fortune cookie, and the lion dance.

Rather than celebrating this migrant culture, the writers belittle its importance and seem to argue that it is a whitewashed culture that doesn’t represent China. The “real” Chinese culture they prescribe is Beijing culture – dragon dance instead of lion dance, using WeChat instead of WhatsApp to exchange greetings (this is the more bizarre suggestion), and saying “Xīn nián kuài lè” instead of “kung hei fat choy”. The articles also omit the fact that the Lunar New Year is also celebrated by Vietnamese, Tibetan, and Korean communities, with their own traditions.

I have read the same “xin nian” suggestion from several Chinese-Indonesians on social media. For these Indonesians, I assume that they are excited to learn Mandarin and Chinese culture, and after hearing from teachers and friends that the popular “Gong xi fat cai” is a common mistake, they would like to spread the correction and send greetings the way Mandarin speakers do.

But seeing two articles in prominent Western media belittling migrant Cantonese culture, I suspect something sinister. I am afraid that the Chinese government is orchestrating a campaign to demean migrant culture, starting with Cantonese culture in the West, while appropriating the progressive concepts of whitewashing and cultural appropriation.

Therefore, both articles drew anger from British and Australian Chinese, who felt insulted. The Cantonese culture in the UK and Australia is not manufactured by the Anglo-Saxons, but is a legacy of their struggles to survive in new lands, and eventually becoming Britons and Australians. It is infuriating to suggest that they have to change this culture to “please visitors from China”. The articles themselves seem to be addressed to white British and Australian readers, ignoring the existence of the Chinese and other Asian diaspora who understand their cultures better than the writers.

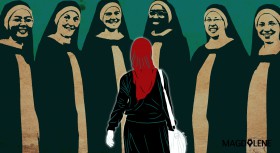

The implication is clear. China is ashamed of the overseas Chinese, southerners who migrated worldwide as coolies in colonial mines and ports, and then mixing their cultures with Southeast Asian, African, Caribbean, and European cultures, while inventing new traditions like the fortune cookie and Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do. Now that China is a rich and respected country, the government and the upper-middle class want to standardize the Chinese culture according to elite Beijing culture – Mandarin language, homogeneous culture, and the global recognition of Chinese people as distinguished tourists and investors instead of takeout restaurant owners and struggling shopkeepers.

Intersectional feminism has helped me being proud of my Peranakan Chinese heritage – my biracial blood, the similarities and diversity of food, dresses, and architecture across Indonesia and Southeast Asia thanks to Chinese migration, and interaction with other races, religions, and cultures. No longer do I wish to understand Mandarin (learning Swedish instead), no longer do I wish to be accepted by other Chinese-Indonesians and believing that I have to associate with other commentators on Chinese-Indonesians.

Instead, I am worried that China’s attempt to homogenize Chinese viewpoint has also started here. To my dismay, some Chinese-Indonesian academics have published articles advocating younger Chinese-Indonesians to learn speaking and singing in Mandarin, following Chinese media, and cooperating with Chinese business and academics, so they can be the “bridge of China-Indonesia friendship.” I find such advocacy disgusting, especially when Xi Jinping is trying to extend his presidential mandate, basing his power on sexism, and after the Chinese Foreign Ministry defended a racist sketch on televised New Year Gala.

I want to know what motivate the Chinese journalists and the Chinese-Indonesian academics to support People’s Republic of China uncritically. National and racial pride? Belief that China is a better option to Western and Indonesian societies? Sponsorship?

Where ever I will live, I will be seen as a Chinese, and my primary identity will always be a Chinese-Indonesian – even if I am no longer an Indonesian. I am happy that the Indonesian government and society have let me carry this identity, and now the Chinese government better take note: We, the Chinese diaspora, define our own identity.

Read Mario’s take on the Criminal Code Revision and the excessive fear of romantic sex and follow @MarioRustan on Twitter.

Comments