Feminism in India combines its commentaries on issues like gender, sexuality and body image with those relevant to the country’s context such as caste, religion, and class issues. The award-winning web magazine says it aims to “learn, educate, and develop feminist consciousness among the youth”.

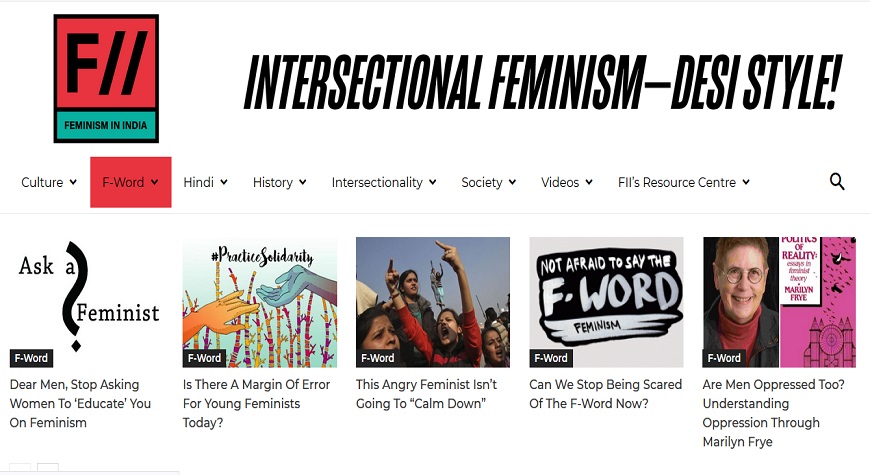

Their “F-word” category, for instance, puts the spotlight on the word “feminism” and peels it off layer by layer to educate the readers on what it actually is and what it stands for. Some of the recent articles under the category sharply tackle real-life issues, such as whether you can still be a feminist when you hate your mother, whether men’s oppression can be measured the same weight as women’s oppression, whether the arts should be separated from creators who are sexual predators and more.

One of the most compelling pieces intersecting feminism, caste, and religion talks about ironies in a nation where a cow is more well-protected than women, despite the fact that according to their belief, cow symbolizes motherhood and femininity. The article points at mob lynching, murder, and rape cases targeting Muslim women who were “suspected” of eating cow meat. It also covers political issues in a country where cow vigilante attacks mark the rise of Hindu-nationalists.

Another gripping piece tackles a discriminative law that bans women in their menstrual ages (age 10 to 50) from entering and praying at Sabarimala temple—one of the largest Hindu pilgrimage centers in India. The law is deemed unconstitutional, as it discriminates a group of citizens, and many women have protested against this ban. The struggle continues as lawmakers lean towards the myths, traditions, and Orthodox Hindu texts that rule that women in menstruating years are impure and distracting.

You might also want to check out its coverage on the condition of women in rural areas, such as the harrowing story of elderly widows who are denied the pension money of their deceased husbands because of red tape issues, and how the Indian government categorizes menstrual pads as “luxury” products resulting in many women in rural areas being unable to afford them. In addition, many Indian women are not aware of the importance of maintaining hygiene in their private areas, partly because they are taught that menstruation blood is dirty, so it doesn’t warrant spending on menstrual hygiene products.

Some of the struggles being talked about in the online platform are relatable to the situation in Indonesia, so check them out and follow their Twitter handle for recent updates.

Find out here how religious minority victims of persecution in Indonesia are denied their basic rights.

Comments