To many families moving to a new place can be an unsettling experience, but when you add religious zealotry to the equation, the impact can reach epic proportion, as Naila’s family has experienced from their two years living in Syria.

Their story started in 2014 in Batam, where Nailah’s father worked for many years as a civil servant. Around that time Nailah’s younger sisters fell for the promises and propaganda of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) caliphate.

“She was introduced to it by one of our uncles,” said the 24-year-old woman who has asked Magdalene to not reveal her full name. “Since then, my sister was curious and learned more information. One of them was from the blog ‘Diary of a Muhajirah’ on Tumblr. She got to know a woman from there and eventually ended up getting brainwashed,”

Seventeen years old at the time, her sister bought into the propaganda that “life in ISIS caliphate is guaranteed to be just like the time of the Prophet Muhammad,” Nailah said. Also, those who joined ISIS would live in a fair and just country, earning big salaries that were free from taxes, and getting free health services, as well as gas and water. Her eager sister spread the propaganda to her parents and even their extended family, along with the invitation to move.

“An uncle of mine had a lot of debt. His company had gone bankrupt. ISIS promises to pay for all his debtd on one condition: that he would go there,” said Nailah in her interview with Magdalene recently in Depok, where her family lives.

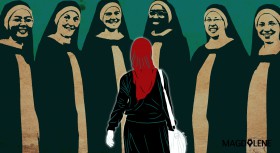

Although they had doubts, Nailah, her parents and two sisters, and some of her relatives left for Syria in August 2015. It wasn’t long before they were disappointed with what they found, and one of them was ISIS’s violent treatment of women.

“They kept data on single women, divorcees and widows and gave them to the ISIS combatants to pick. These combatants would proposed to the women in the morning and demanded their answers later on in the day,” she said.

“My sister was proposed to a few times, luckily, she could reject them. One ISIS combatant wanted to have more wives, even though he just got married a week before,” she added.

Her aunt experienced worse. One time she was caught wearing clothing that was deemed un-Islamic by the ISIS police. She was dragged into a police car and brought to a building where she had to take off her clothes and buy new ones.

Eventually, Nailah’s family decided to leave the false utopia they had been promised.. After a year and 10 months, they finally managed to escape the ISIS areas, and in August 201 they returned to Indonesia.

In Taiwan, Indonesian migrant worker Dian Yulia became radicalized online and believed suicide bombing is a part of the holy war. Someone she knew on Facebook introduced her to Nur Sholihin, an ISIS supporter, whom she then married. The marriage was in part a strategy for her to carry out her mission, because she was taught that women needed the permission of her husband to carry out any activities outside of their home.

Three months after their marriage, the couple hatched a plan to bomb the Presidential Palace in Jakarta. The police caught on the plan, however, and they were arrested in Bekasi in December 2016.

Transformation of women’s involvement in terrorism

Both Nailah’s sister and Dian Yulia show how women are targeted in the ideological battle of radical religious groups in the last decade, but the role of women in terrorism is not a new phenomenon. Before ISIS’s existence, women played supporting role in the Jamaah Islamiyah (JI) circle – a terrorist group affiliated with the international terrorist organization Al Qaeda.

“In its history, especially in the Afghanistan War (in the 1980s), women were involved as supporters of the Indonesian jihadists who travelled there. Sometimes as a mother, sometimes as a wife,” said Lies Marcoes, an Islamic and gender studies scholar who is also the Executive Director of the Rumah Kita Bersama Foundation (Rumah KitaB).

During the transition from JI to ISIS, this supporting role began to shift.

“When the United States policy towards terrorism became stricter, JI found it difficult to move. Because of this, they started to involve women by giving them more ‘masculine’ roles, like spying or bank hacking, which used to be done exclusively by JI’s male members,” said Lies.

From the start, ISIS has a different perspective towards the involvement of women. In January 2015, a manifesto was spread on the internet released by Brigade Al Khansaa, an ISIS militia that had female members. The document stated that although the main role of women are as mothers and to be of service to their husbands, they were allowed to take up arms in some situations.

A researcher of the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC), Dyah Ayu Kartika said that Bahrun Naim, an Indonesian higher-up in ISIS, once had a mission to encourage women to become a suicide bomber.

“The reason was that women would not be suspected to carry out a terrorist act, while, at the same, if an attack is committed by a woman, it would be covered more massively by the media than if it is done by a man,” she said.

Alimatul Qibtiyah, a professor of Gender Studies in the National Islamic University (UIN) Kalijaga, Yogyakarta, said that radical groups have tried using the gender stereotype that women are considered passive and it is impossible for them to be involved in an act of violence.

“To them, using women is more effective to conduct an amaliyah (terror act),” said Alimatul, who is also a commissioner at the National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan).

The National Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) recorded that the number of women involved in terror acts has risen from 13 people in 2018 to 15 people in 2019. This includes the suicide bombing of Abu Hamzah’s wife in Sibolga, North Sumatera in March 2019.

Also read: To Fight Radicalization in Southeast Asia, Empower the Women

A research by IPAC in 2017 titled “Mothers to Bombers: The Evolution of Indonesian Women Extremists” shows that other than being possible suicide bombers, Indonesian women can also conduct fundraising for terrorist acts. Ika Puspitasari was arrested by the Special Detachment (Densus) 88 Anti-terror Police of the Republic of Indonesia a few days after Dian’s arrest. In October 2017, she was sentenced for funding some planned terror acts coordinated by her husband.

The suicide bombing in Surabaya on May 2018, which involved married couple Dita Oepriarto and Puji Kuswanti and their four children, has also showed a change in ISIS’s approach by recruiting a family as part of its terror agenda.

But many still do not fully grasp this. Lies Marcoes said: “The involvement of families and women is seen as an anomaly by the state. They believe that violent extremism is a man’s world. Their analysis tool fails because they do not consider gender perspective and feminism, therefore they do not see the reality of how women can be involved.”

Issues Surrounding Rehabilitation

The ISIS caliphate did not last long. Eventually they lost much of the areas they controlled as they fended attacks from numerous parties. Many who joined them have returned to their respective countries, either as a returnee or a deportee.

The term returnee refers to people who managed to enter the Syrian territory and returned voluntarily. While deportees are those who did not succeed in entering Syrian territory because they were arrested by the Turkish authorities and were deported. Those who were returned to Indonesia (mostly from Singapore and Hongkong) because of their activities as an ISIS supporter are also considered as deportees.

There were at least 500 deportees and returnees arriving in Indonesia since January 2017 to mid-2019. This data was recorded by the Civil Society Against Violent Extremism (C-SAVE), a network of civil society organizations that focus on issues of terrorism, from the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT), the Center for Social Rehabilitation of Children in Need of Special Protection (BRSAMPK) “Handayani” and the Bambu Apus Protection House and Trauma Center (RPTC). The reasons for their departure varied, from religious beliefs to the desire to find a better-quality life. A whopping 78 percent of deportees and returnees are women.

“C-SAVE identified 10-15 percent of those who returned or deported as female migrant workers who were recruited overseas. Most of them became migrant workers to flee domestic violence or family conflicts at home. Abroad, they felt lonely and sought peace in religion. Unfortunately, they were trapped in the wrong group,” said Mira Kusumarini, the Director of Yayasan Empatiku and the former Director of C-SAVE who has accompanied deportees and returnees.

The government’s program to deradicalize and to socially rehabilitate deportees and returnees is under the Ministry of Social Affairs (Kemensos). Women and children are placed in BRSAMPK Handayani, while the adult men are placed in RPTC Bambu Apus. The rehabilitation program and deradicalization also involves the Ministry of Religion, BNPT, and psychologists.

Although many female deportees and children are not from the Greater Jakarta area, the social rehabilitation activities are focused in Jakarta due to the lack of facilities and skills of social service workers in rural areas to support the program.

Mira from Yayasan Empatiku said in the process of reintegration, C-SAVE tries to incorporate gender mainstreaming. The assistance is also conducted for female returnees looking for a source of income after their husbands have been sentenced to jail for involvement in terrorism.

As for Nailah, after her reintegration process went smoothly, she has begun to share her experience to show people the danger of violent religious ideologies.

“I was involved with the Yayasan Prasasti Perdamaian (YPP) and the Aliansi Indonesia Damai (AIDA) for talkshows in events that had an anti-terrorism theme at schools,” Nailah said.

“We realized we have made a mistake, but these institutions did not judge us for it. I feel more confident and I get to learn a lot. I also learned to empathize more because I get to interact with bombing victims,” she said.

Nailah got a job thanks to her and her sister’s involvement with these organizations. She was recruited to draw comics after her sister talked about her talent to a digital media. In one event she was participating, Nailah was introduced to a bee product distributor who then offered her to join the company.

But reintegration remains hard for most returnees and deportees because of the stigma attached to them.

One school has felt the impact of this after accepting the daughter of a female deportee.

Said Mira of Yayasan Empatiku: “The school principal told us that the student registration has gone down because the institution is labeled as a terrorist school,” Mira said.

Prioritizing Gender Mainstreaming

The involvement of women in terrorism should be responded with more gender-sensitive policies. While being investigated as a witness, Nailah was questioned by a male police officer.

“The interrogation process should be more gender-sensitive. If women were interrogated by male police, they might be intimidated,” said Mira.

And it’s not for the lack of female police officers. Even if female police officers were present, they would not be given more responsibilities because of patriarchal mindsets. “’You’re a woman, why are you guarding the cells at night?’” Mira said, quoting an example.

The presence of female police officers is very important. Allison Peters, in a policy brief entitled “Countering Terrorism and Violent Extremism in Pakistan: Why Policewomen Must Have a Role” argued that recruiting more women and promoting them to decision-making positions should be a priority for law enforcement institutions in the framework of countering terrorism.

BNPT’s Deradicalization Director Irfan Idris, dismissed the notion that his institution was not gender sensitive. He cited the time when they handled the case of Minhati Madrais, the wife of Omar Khayam Maute, the leader of a pro-ISIS group who died during a military operation in Marawi, Philippines.

Also read: To Fight Radicalization in Southeast Asia, Empower the Women

“Many did not understand how to handle Minhati, who was deported from the Philippines. So they accused ( our deradicalization program) of lacking (gender perspective),” said Irfan in an interview with Magdalene through WhatsApp messaging. He did not elaborate further.

There’s no denying, however, that BNPT is still dominated by men.

“There are no women at the deputy or director level positions. The highest position held by a woman is as Head of the Sub-Directorate for Community Empowerment, which is held by Mrs. Andi Intang,” said Ruby Kholifah, Director of the Asian Muslim Action Network (AMAN) Indonesia.

The absence of gender perspective in deradicalization process will make it difficult for disengagement, which is the process during which a person or a group of people no longer commits violence, leaves the terrorist group, or changes their roles.

“If BNPT does not understand the personal trajectory (of women), then they would find it difficult to distinguish handling of men from that of women. Many women are engaged with terrorism because they face gender inequality. By understanding the causes of radicalism, the solution for disengagement would be required,” Ruby said.

Lies Marcoes from Rumah KitaB said, the state-run deradicalization process was still done through the approaches of nationality, religion, and entrepreneurship.

“Gender and feminism analysis explains the diverse motives that depends on numerous situations. Do your research first and do not make a program without a good foundation. The research needs to have a feminist perspective for a clearer perspective on women,” she said.

Another issue is that the absence of the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection’s (KPPPA) involvement in the handling of deportees and returnees.

“KPPPA is the leading sector in gender mainstreaming, it should not just be a complement (to these issues). Without KPPPA, other Ministries would have weak gender perspectives in analyzing violent extremism,” Ruby said.

KPPPA has the Integrated Service Center for Women and Children Empowerment (P2TP2A) and the Regional Technical Implementation Unit for the Protection of Women and Children (UPTD PPA) which should function as a rehabilitation center.

“The rehabilitation carried out by BRSAMPK Handayani did not take long. It is very rare for someone’s perspective to be critical again after being exposed to radicalism. To carry out rehabilitation only at the center is not enough,” Ruby said.

Some have continued to advocate for the inclusion of gender perspective, one of them is in the Draft Presidential Regulation on the National Action Plan for Combating Violence-Based Extremism that Leads to Terrorism (RAN PE).

“BNPT links gender with prevention, which is totally wrong. When we talk about gender, we are referring to the construction of power relations in a certain case. On the issue of violent extremism, it is important to understand that being a woman in the context of extremism is different from just the usual context,” Ruby said.

Ruby also emphasized that after this RAN PE is passed by the President, there must be at least 30 percent representation of women in the working group. Without it, it would be very difficult to keep the perspective,” she said.

This coverage was funded by the “Peace Journalism Fellowship” grant from Harmoni that was organized by Search for Common Ground Indonesia and the Journalists Association for Diversity (SEJUK)

Comments