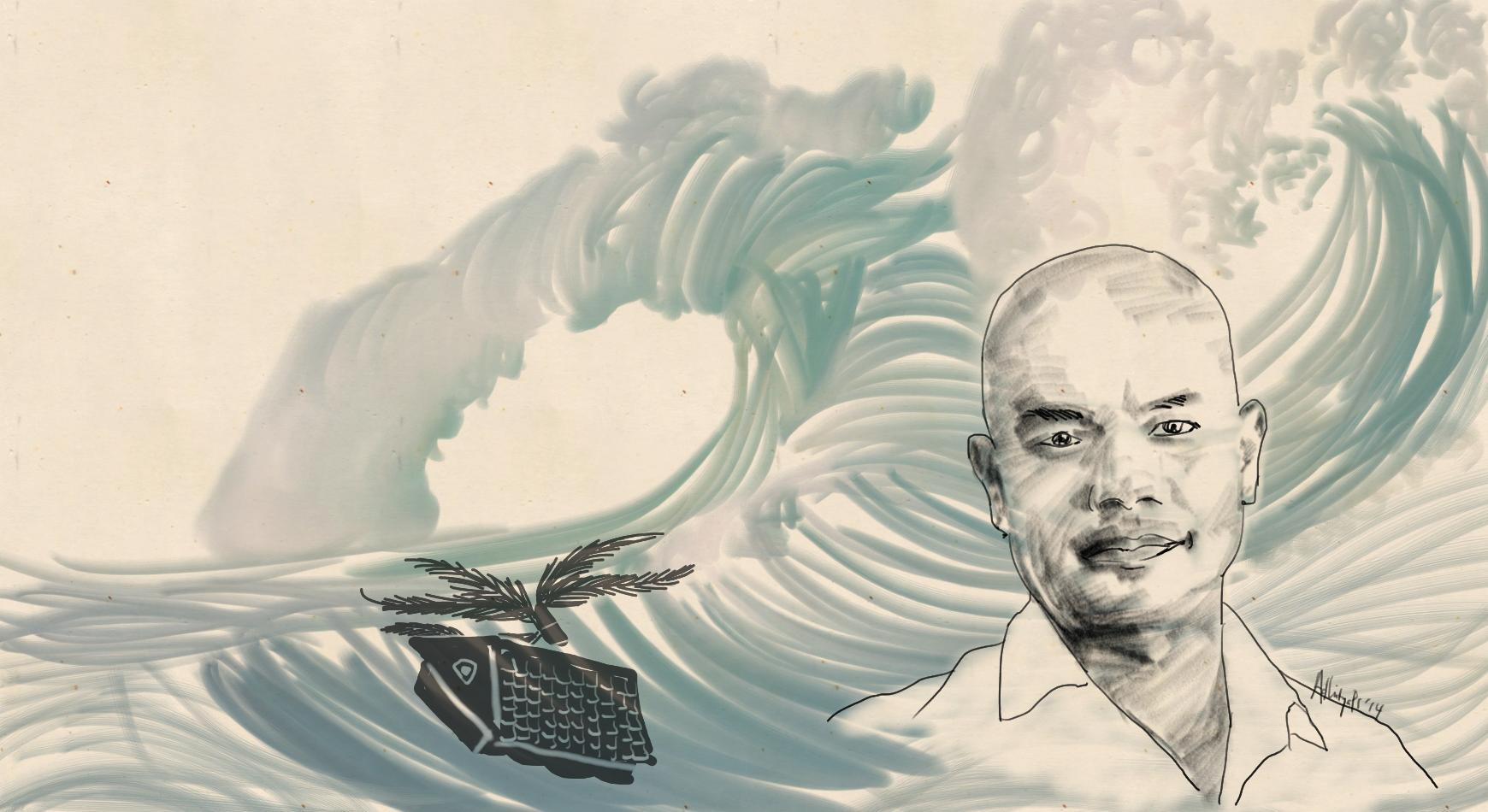

I was tiptoeing on a coconut log when I suddenly lost my balance and fell into a black puddle where a mangled buffalo was floating. I extended my right hand into the air, making sure the hand-held video camera stayed dry.

My travelling companion, photographer Beawiharta a.k.a. Bea, screamed from a distance to find out if I was okay. Standing in waist-deep water – in a Statue of Liberty-style pose – I realized that I had mastered the art of keeping our reporting devices safe.

Bea and I were in Leupung and we had been walking silently along this tsunami-battered coastline of Aceh for nearly 20 minutes, and had not met a single soul.

Armed with biscuits and water, we wanted to reach the area where the aid had not reached, so we went as far as the motorcycles could go and started trekking. The 9.1 on a Richter scale earthquake had destroyed much of the coastal roads, making them impassable for vehicles.

The only sound we heard was the crashing waves, which added to the eerie atmosphere of death. I had on a facemask, which failed to fight off the lingering odor of corpses and dead livestock, some of which in full view of our walking path.

Also read: Washed Away, Rescued, Kidnapped and Struggling: A Tsunami Survivor's Life

It was a perfect day with clear blue sky and the cool sea breeze gave much-needed respite to the heat, but the paradise had been turned into a quiet hell, scattered with remnants of life. Among the mountain of debris, shoes and colorful toys sticking out along with legs and arms, I saw a framed picture of a family shot in a studio.

It was New Year’s Day 2005, and we had been in Aceh for nearly a week. Earlier in the day, the electricity was restored and I watched the morning news on the fatal shooting of a waitress by conglomerate Adiguna Sutowo at a nightclub owned by his family. I remember watching the news with disgust and hurled angry remarks at the TV. Our host Nunuu Husien, a native Acehnese who lost her father in the tsunami, stood behind me. We met her at the airport when we landed in the morning of December 27 – a day after the tsunami hit Aceh.

The reporting saga began even before we touched down in Aceh. Most passengers aboard the A-300 Garuda ignored the seat belt sign and huddled to the windows to see water-inundated homes. A palpable sense of grief swept through the plane as I heard sobs and wails of “Allahu Akbar.”

At the airport, loud cries and sobs echoed through the arrival hall as passengers and relatives rushed to embrace.

“Are you a journalist!? Please tell the whole world what happened in Aceh. Come with us!” Nunuu spoke to me as I stood there feeling dazed and confused. I had never in my entire life as a journalist felt a very strong sense of purpose.

Our first stop was the Lambaro roundabout where we saw hundreds of corpses laid outside the Red Cross office. I had been working with editors who were obsessed with figures and color.

“If you can, try to count the number yourself,” the late Jerry Norton, one of my editors, would tell me in his dry tone.

So, I walked among the bloated corpses because I had to see what they looked like. I kept saying “Permisi” (excuse me) as if they heard me, but that was my foolish attempt not to be disrespectful. I looked closely at their disfigured faces, some mouths became so oversized they seemed to overtake the faces they inhabited.

I may have cringed but I did not look away because I had to describe the scene down to every little details. I did wonder whether the world needed to see these gory details, should these details stay locked in my brain?

This was the first of countless scenes I would tell my editors in Jakarta during my first tsunami trip to Aceh. Every hour I called my them through a satellite phone, reading out notes in my notebook, which contains quotes, colors, facts and figures on loss, despair and horror.

I kept looking for open fields to get unobstructed coverage for satellite phone and I would desensitize every survivor’s stories into mere words of facts. Often my editors asked me to pause as I described the death scenes and the harrowing account. Worrying that we might lose connection, I reminded them to press on. Looking back, I felt I was holding back too much and tried too hard to put up a clinical demeanor.

But the memory of my first day remains the strongest.

Also read: How the Tsunami Brought Me Home to Rebuild It

I remember lending my satellite phones to several men and women, desperate to tell their loved ones of their fate. One woman wailed, collapsing to her knees as she talked on the satellite phone while an anxious looking man stood beside me, waiting for his turn. I had to turn down many because with no electricity we had to be efficient with our phone usage.

I circled around the city inside a Mobile Brigade police truck that went on a patrol to collect the wounded and the deaths. One person appeared to have lost his life aboard the truck, after residents found him alive among the rubbles of Aceh Raya market.

At the city’s military hospital, a middle-aged woman sat on the floor – her face covered with fresh scars and her legs bandaged – reached out to me and said, “Please help me Nak (son)”. I lowered myself to hold her hand but I did not say anything. I did not say a word, not even a word of comfort because we were in hell and I wasn’t sure whether we’d be okay. Then one of the policemen called out my name and I rushed back to the truck as we resumed the patrol.

I spent my first night at Ibu Nunuu’s house – crowded with her surviving relatives – wide awake, thinking about the horror I witnessed. But mostly I thought about the woman at the hospital. What a horrible human being I was, I thought to myself. I could’ve hugged her, I could’ve comforted her, I could’ve done the things that any compassionate human being would do. Instead I rushed back to the truck to resume my reporting duties.

The memory of my first tsunami trip is locked safely in a time-proof steel box inside my brain. I would replay the event in my head and the same vivid harrowing details would play out.

Back to our little adventure in Leupung, we finally met a group of people who had been walking for days from their hometown in Calang. They survived on nothing but coconut water, so Bea and I gave away our biscuits and water. One vision that remains etched in my brain is the one when a toddler took the biscuits from my hand without saying a word. He neither looked sad or no happy. I did not talk to him nor asked for his name.

I spoke to one survivor with a T-shirt around his mouth – it was his version of a facemask. The stench of the corpses was worse at night, he said.

Ten Years After Tsunami

For 10 years I never revisited these scenes. I never wanted to share my experience into words. As a journalist, we are taught to report the story of others – not us. But a recent visit to Aceh has given me a change of heart.

Aceh now shows no trails of destruction. Makeshift camps that once dotted the ruins of the city gave way to buildings and houses. Banda Aceh is paved with wide, smooth roads – much smoother than the pothole-ridden roads of Jakarta, which can be a death trap for motorists.

And then there are the people, particularly the tsunami survivors.

I recently met a group of farmers who have been back at the paddy fields after their land was cleared from tsunami debris. I spoke to a couple of businessmen who make a living out of recycling waste after years of selling steel from the tsunami waste.

The memory of my first tsunami trip is locked safely in a time-proof steel box inside my brain. I would replay the event in my head and the same vivid harrowing details would play out.

After recently speaking to the survivors and seeing how Aceh has become, it’s hard to believe how the past scenes of horror could actually turn into the Aceh that is today.

Not all the details in my reporting made it into the story. Perhaps I was being a little too obsessed with color and I shouldn’t have walked among the corpses in Lambaro. I probably will not meet again those whom I interviewed and I still wonder about the fate of the woman at the hospital and the cute toddler who took my biscuits.

But seeing how Aceh has become now, I have grown a little hope in my heart that maybe; just maybe they are now back on their feet.

Comments