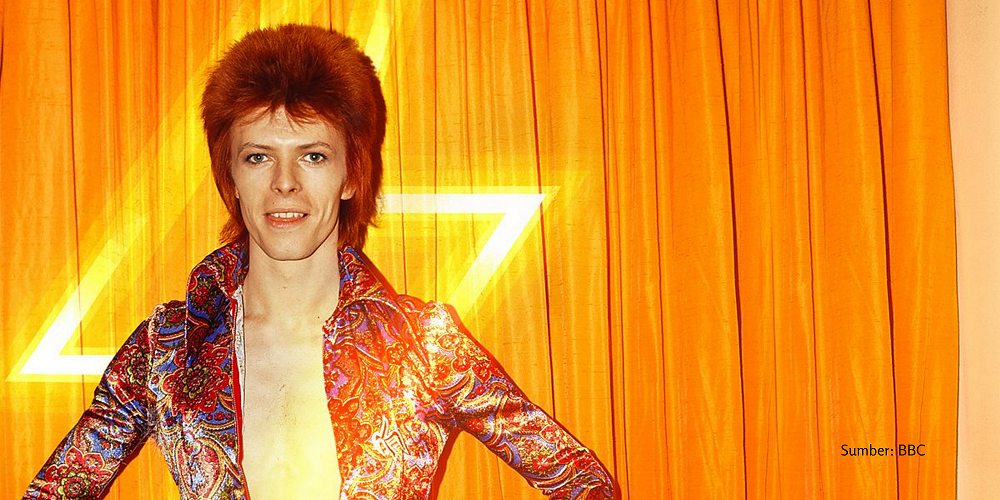

David Bowie released his seminal album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars 50 years ago, on June 16, 1972. It was an artsy and ambitious rock album which captured the time’s sense of being on the cusp of new technological and cultural frontiers.

In the early 1970s, the US Apollo programme was, briefly, making men visiting the moon seem like a routine event. The possibilities of computer power were beginning to unfold, and the countercultural youth revolt was challenging prevailing values and norms. Bowie’s fictional alter ego encapsulated all these groundbreaking developments: an androgynous rockstar from outer space with, in the words of the album’s title song, “a god-given ass”. Bowie-Ziggy wore heavy makeup, dyed his hair red, and dressed in clothes inspired by Japanese kabuki theatre.

But coupled with its playful fascination for space technology, the Ziggy Stardust album also described a dread of the Pandora’s box that might be opened as a result. Its opening track, Five Years, warned listeners that “Earth was really dying”. During the cold war, the prospect of man-made armageddon through nuclear war was never far away. And by the early 1970s, fears of an ecological crisis and overpopulation were starting to take on similar apocalyptic proportions.

Indeed, the day of Ziggy Stardust’s release coincided with the final day of a landmark gathering in Sweden to discuss the future of the planet. The Stockholm Conference, which began on June 5, 1972, was the first United Nations conference on the human environment, and the starting point for global environmental governance.

Today’s global climate summits, most recently COP 26 in Glasgow last November, are its direct descendants. And like Bowie’s album, the Stockholm Conference began amid conflicting emotions: hopes of a new dawn of environmental awareness and technological possibility set against fears of global conflict and planetary collapse.

Also Read: If I Were a Boy, How Easier My Life Would Be. Here’s Why

Moonage Daydream

Bowie’s obsession with outer space predated the creation of Ziggy Stardust. In June 1969, what would become his first major hit single, Space Oddity, was released. It told the story of an astronaut losing contact with Ground Control while gazing at the Earth from afar in his “tin can”. In July 1969, the BBC used the song in its broadcast of the first moon landing, apparently unaware of the tragic lyrics.

As Bowie clearly grasped, the Apollo space programme was central to the birth and early growth of the global environmental movement. It was during the manned moon expeditions that Earth was first photographed from space. The most iconic image, “Earthrise” – taken over Christmas 1968 with a Hasselblad camera by the crew of Apollo 8 – shows our planet rising over the lifeless landscape of the moon, like a sun at the horizon. It has become one of the most widely shared and reproduced photographs of all time.

Astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell and William Anders had become the first humans to venture outside the Earth’s orbit. New satellite technology also made it possible for their space adventures to be followed via television broadcasts. On Christmas Eve, they read the opening verses of Genesis and sent festive greetings to an estimated one billion people watching around the world. Six months later, the first moon landing drew an even greater audience, offering those watching further spectacular views of the Earth.

Such images resonated among the new breed of environmentalists. In the words of historian Robert Poole, “It gave people a picture to think with.” Other scholars talked about the “overview effect”: by seeing the Earth from space, people became aware that life on their planet was interconnected, limited and vulnerable – giving impetus to the emerging survivalism movement.

The opening track of Ziggy Stardust, Five Years, echoes some of the survivalist debate’s darker sentiments, with its weeping “newsguy” confirming the end of the world is nigh. Yet just five years earlier, during 1967’s utopian summer of love, this message would hardly have resonated in popular culture.

In Swedish history, the pivotal moment for the awakening of environmental consciousness came in the autumn of 1967. At that time, a choir of prominent Swedish scientists publicly warned of an impending global environmental crisis. Foremost among them was the chemist Hans Palmstierna, whose book Plundering, Starvation, Poisoning became an instant bestseller. Palmstierna argued there was an urgent need to act “before the hourglass expires for humanity”. He linked environmental destruction to other global issues, including world poverty, war and overpopulation – thereby emphasising that environmental hazards were just as severe a threat to humankind.

The impact of Palmstierna’s and other scientists’ collective intervention was powerful. There was talk of a general environmental awakening in Sweden, as the national press, radio and television reported on mercury-poisoned fish, biocides and acid rain with unprecedented intensity.

In the words of the Swedish historian Lars J Lundgren, it was as if a “new continent of problems” had been discovered. Where previously, environmental hazards had been regarded as individual problems to be solved in isolation, more and more people were beginning to see them as connected – and constituting a severe crisis.

Also Read: Gender Fluidity Is Great - But Only If You're Famous

Five Years

From an international perspective, Sweden’s breakthrough of environmental concern occurred remarkably early. Intrinsic to this reorientation was the very concept of “the environment” (in Swedish, miljö).

The word had not been used in the early 1960s – for example, during the intense debate sparked by Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which awakened public understanding of the links between industrial pesticides and the die-out of insects and wildlife in the US. At that point, people discussed nature, conservation and the threat modern industrial civilisation posed to wild birds and animals. But the environmental debate which arose in Sweden in the late 1960s put the threat to humankind at the forefront.

The discovery of acid rain was of particular importance. The finding that it was being caused by sulfur dioxide emissions from across Europe was first reported in October 1967, in an article in Sweden’s largest morning paper, Dagens Nyheter, by the scientist Svante Odén. The story caused an immediate stir and frantic political action.

Inspired by the debate at home, Swedish diplomats suggested to the United Nations that a large environmental conference should be organised. Their initiative set the ball rolling towards what would eventually become the 1972 Stockholm Conference, the UN’s first global Conference on the Human Environment.

Over the intervening five years, the Swedish public became acutely aware of the Earth’s environmental crisis – a chain of events I examine in my book, The Environmental Turn in Postwar Sweden: A New History of Knowledge. A key voice in this national debate was Gösta Ehrensvärd, professor of biochemistry at Lund University, who calculated that the depletion of the planet’s limited resources, combined with accelerating population growth, would lead to a global crisis in around 2050 – followed by centuries of famine and anarchy.

Ehrensvärd was accused by his opponents of being a gloomy doomsday prophet. But he saw it differently: “Planning to clean up the Earth’s affairs in the long term is realism, not pessimism.” What was needed, he said, was to steer development in new directions, and to take precautions against overexploitation and natural destruction. This would require “an array of technological expertise, wisdom, humanity and foresight” – and he hoped the Stockholm Conference would be a step in the right direction.

It Ain’t Easy

Half a century ago, in the summer of 1972, the future of humanity was looking increasingly precarious in many other ways, too. In the US, the racial divide and ongoing Vietnam war spurred civil unrest. On a global scale, in addition to the cold war, the process of decolonisation highlighted stark differences between the global north and south. Threats of overpopulation and dwindling natural resources were made real by catastrophic famines in India and Biafra.

Despite the Stockholm Conference’s focus on humankind’s shared destiny, it – like the world – was deeply polarised. With East Germany barred from participating because it was not a member of the UN, most of the Eastern Bloc announced they would boycott the event. (The only communist countries to attend were Yugoslavia, China and Romania.) The conference was also sharply criticised by emerging environmental movements who argued it was a top-down, inadequate and purely symbolic event. Parallel environmental conferences were organised in Stockholm, such as the radical left-wing People’s Forum.

The main conference’s inaugural speech by Sweden’s prime minister, Olof Palme, was also controversial. He highlighted the “tremendous destruction caused by indiscriminate bombing” and “the large-scale use of bulldozers and herbicides”. Although not stated explicitly, there was no doubt his remarks were aimed at US conduct in Vietnam, which included use of chemical herbicides and weather modification technologies that were elsewhere described as “ecocide”.

Palme’s speech was not appreciated in Washington. A spokesperson for the US state department said that “deep unease” was felt over the way the prime minister of the host country had raised this issue, which (in US eyes, at least) had nothing to do with the environmental protection conference.

The discussions in Stockholm went on for two hot June weeks, based on a growing realisation that humans were on the verge of destroying their own living environment. While the assembled world leaders sought to instil hope and spark international commitments, some environmental activists objected that the conference was excluding the general public. It only existed, one wrote, so that “the real decision-makers” could meet and discuss “the problems they themselves have caused”. On a diplomatic level, however, there were reasons for optimism, with the People’s Republic of China – having been admitted to the UN in October 1971 – making its first appearance on the global scene.

Two concrete results of the conference were the Stockholm Declaration, which laid the groundwork for international environmental jurisdiction, and the foundation of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP). Based in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, UNEP became responsible for coordinating international responses to environmental issues, and was the first UN body located in the developing world.

Much of the conference’s focus ended up being on the global north-south divide. The western world’s efforts to deal with environmental degradation and overpopulation were pitted against developing countries’ desire for industrialisation and prosperity. Knowledge of an ongoing environmental crisis was circulating globally by now, but it was understood and handled in very different ways by the conference’s various power blocs and countries.

To an observer in 2022, with last year’s COP26 still fresh in the memory, the dividing lines of Stockholm 1972 look eerily familiar. Then, as now, young environmental activists viewed the conference as a slow and insufficient way of dealing with urgent problems. Greta Thunberg’s famous “blah, blah, blah” speech could have been spoken by protesters in 1972. Fifty years on, we have grown accustomed to recurring meetings, declarations, goals, bleak scenarios and calls from scientists and environmental activists to change the system. Much of this was present at the birth of global environmental politics.

Also Read: Five Reasons Andy Warhol is So Popular Right Now

Starman

Göran Bäckstrand had not long been working at the Swedish foreign ministry when a telegram from the Swedish delegation to the United Nations landed on his desk. They had just put forward the idea of a UN-led conference focused on the environment. Over the next five years, Bäckstrand was directly involved in the preparation and organisation of the 1972 Stockholm Conference.

Now in his mid-80s, Bäckstrand remains a vigorous and politically engaged figure. Over the last five years, we have discussed environmental history and contemporary concerns both in-person and over the telephone. He is a joyous soul who does not seem to despair – even though the road ahead has proven “far longer and more complicated than we imagined in 1972”.

“My vocation for international relations got an essential new twist by being part of the Swedish team preparing the substantial scientific input for that conference,” Bäckstrand recently told me. “At one point, Professor Bert Bolin [who later became the first chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)] presented a preliminary report to our minister for the environment. He asked Bolin if he was 100 percent sure about the predictions in the report. Bolin said ‘no’ as there were too many variables to consider, and the minister remarked that he had always to be 10 percent convinced in proposing political action.

"To me, this illustrates why decisive political action on climate change has been neglected.”

Looking back, Bäckstrand thinks the most important result of the Stockholm Conference was helping to build a “global environmental consciousness”. It also created a framework for environmental governance at an international level and indirectly led to the founding in most states of national environmental authorities.

This June 2-3, the 1972 event will be commemorated in the Swedish capital during Stockholm+50, a UN conference jointly organised by Sweden and Kenya. Its organisers are seeking to highlight the importance of multilateralism in tackling what they call “Earth’s triple planetary crisis”: climate, nature and pollution. But just as collective action proved difficult at the original Stockholm Conference, is it possible for the nations of the world to act any more decisively now?

Bäckstrand’s expectations are set low – hardened by recurring experiences of gruelling international climate negotiations. Pondering the developments of the last 50 years, he told me: “In 1972, there existed some kind of harmony between certain aspects of science and politics, and there was a mild confidence among the participating nations of the environmental crisis as a unifying mission.”

Today, he says, the relationship between politics and science is much more problematic, and the environment has become polarising. “There are two parallel processes of the last 50 years: the exploitation of natural resources has accelerated, and trust in the international system, and the constructive role of the UN, has gradually disintegrated.”

Before our latest conversation ended, I had to ask one more question of this lifetime civil servant and globally minded environmentalist. “Did you listen to the new Ziggy Stardust album when it came out that year? And did you feel any resonance with the messages you were discussing in Stockholm?”

“No,” Bäckstrand confessed. “In fact, I have never heard of it until you told me about it now. But I am glad you have made the connection to music history. I think it is an important one.”

Blackstar

The final day of the Stockholm Conference – June 16, 1972 – was the day that Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders of Mars was released to the world. Fifty years on, the hopes and fears evoked in this album, like the conference, still feel disturbingly relevant – particularly amid the heightened nuclear tensions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

So what would Bowie have made of the way things have turned out for the planet? He may have left some clues in his final album, Blackstar, released two days before his death in January 2016. The music videos for the title song and second single, Lazarus, were directed by another Swede, Johan Renck. At the centre of the Blackstar video is an empty space suit, blinking back to the Major Tom character in Space Oddity and Ashes to Ashes – a distinctly gloomy echo of that groundbreaking time when men first walked on the moon.

Bowie’s death coincided with a renewed interest in outer space. In our time, however, it is not superpower states that are leading the way to the final frontier, but superwealthy individuals such as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who have made their billions through the digital revolution of the 21st century – and whose companies and personal fortunes arguably epitomise the staggering inequalities that new technologies emerging in the 1970s have enabled.

Environmentally, the picture feels similarly bleak. This November’s COP 27 will return to Africa in Sharm El-Sheik, Egypt. The continent, despite contributing a mere 4 percent to global emissions of greenhouse gases, is bearing the brunt of their impacts, with the combined effects of severe drought, flooding and pestilence – along with conflict in Africa and Ukraine – now threatening a “full-scale catastrophe” across East Africa.

The challenges facing those following in the footsteps of Bäckstrand and his fellow attendees of the 1972 Stockholm Conference appear daunting, to say the least.![]()

This article was first published on The Conversation, a global media resource that provides cutting edge ideas and people who know what they are talking about.

Comments