I was spared from such chore in early 1990s, though I wasn’t free from similar exposure to the “cruelty” of the communist party members allegedly behind the abortive coup. In Grade 5 my class visited the Lubang Buaya Museum, and saw wax statues of mad communists torturing bleeding generals, complete with horrendous voice clips. At that time my friends were upset with the murder of Christian general D.I. Panjaitan, and the Eurasian officer Pierre Tendean became a fallen idol for the girls. Cold War had ended by the time I visited and Indonesia-China relations had been normalized, yet communist alert remained high in Indonesia.

This alert was meant to be vague – the government didn’t seriously investigate the link between “PKI” with the labor unrests of early 1990s. By then I understood that “PKI” was just a bogeyman to justify military’s grip on Indonesian politics. I believe that movies represent the contemporary mood of their release period, whether it’s set in the past, the future, or in a fantasy world. Though G30S was set in 1965, it must be a movie about the 1980s.

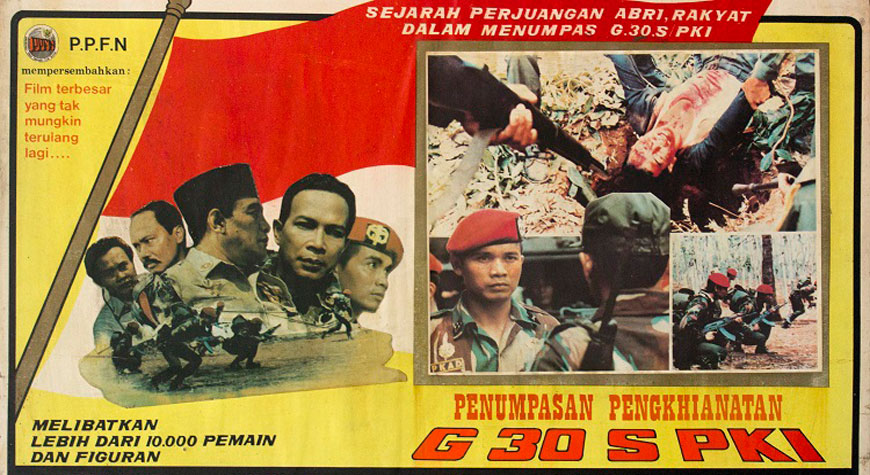

With the Army holding nationwide screenings of the docudrama again this year, I tried to watch it to catch its hidden messages. In my first viewing, I quit after 30 minutes. It was too bloody and boring, and I had to accept the reality that I could never be a film reviewer. For second viewing, I tried to watch the movie while playing Warkop’s 1984 movies and listening to 1984 top hits, but, again, I crashed.

Luckily, I found Dad’s copy of the movie novelization, written by Arswendo Atmowiloto. For the sake of completing this article, I read the novel, and then watched the last hour of the movie, past the abduction and torture scenes.

Comprising three acts, this is how I would describe the movie: Act I of G30S is a mafia meeting, which has been much parodied online; Act II is a traumatizing home invasion – times six; Act III is a Suharto fanfiction, with, surprisingly, some bland action scene. That’s all. This is a dull and pointless movie. The novelization itself convinced me to join NaNoWriMo – if the legendary Arswendo could write such abomination, then I can do better.

Then why was it made?

Suharto faced several problems in early 1980s. A.H. Nasution had openly criticized him in 1980, and the second generation of Indonesians had grown into adulthood. The 1982 election was marred by deadly riots, and instead of socialism, Islamism was the ideology of resistance in universities.

Other Southeast Asian nations faced similar “second generation problem” and also answered with censorship and oppression, as well as reliance on United States’ good grace in the renewed Cold War. G30S was Suharto’s effort to rally the populace to his side.

For Catholics, the movie was a straightforward story of the Passion, with the generals tortured and executed like Jesus, and Suharto resurrecting the light. For Muslims the movie highlighted the brutal murders of santris and the devotion of Suharto to Allah. For the growing middle class, the home invasion scenes were true horrors: Imagine if Dad was abducted or killed in the middle of the night, and baby sister died in your arms. That’s what communists could do to you.

And who were the communists for 1980s’ audience? Activists. Feminists. Liberals. Protesters. Probably even disgruntled soldiers and officers in the military. The conclusion of G30S hints that the communists have become ghosts who are alive well into the 1980s, lurking like devils waiting to tempt faithless human.

When the movie came out, Suharto was fighting a war against the Islamists, who responded to the Tanjung Priok massacre by bombings BCA branch offices across Jakarta, Marine arsenal at Cilandak, and Borobudur. Pancasila became the only legal political ideology in 1985, and the controversial PSPB (History of the Nation’s Struggle) school subject appeared, combining History and Pancasila Studies.

G30S and PSPB, among others, showed that Suharto went all-out to smear the reputation of Sukarno, who was idolized by left-wing and nationalist youth. This is why the screening of G30S was repeated every year, as Suharto tried in vain to make the case that he’s the savior of Indonesia, and that the Army had made the ultimate sacrifice for Indonesia.

Then why does this movie return in 2017? For one, some hawks inside the military (specifically the Army) appear to believe that they are living in hard times. With the idea of a military government having become obsolete, the generals might see being led by a civilian commander-in-chief as humiliating. And while the call for justice for the anti-communist mass killings of 1960s remain strong, Suharto’s children have been more than clear in their intention to “reclaim” Indonesia as can be seen in their participation in the past two elections. They would of course make a natural bedfellow for the more political ambitious in the military.

Joining them are the more familiar villains of religious conservatives. They believe that “godless communists” – represented perhaps by, among others, writers and readers of Magdalene – are destroying Indonesia. They were the ones who pushed for neighborhood screenings of G30S, and felt insulted by memes and pieces questioning the docudrama.

Personally, I’m pessimistic that Indonesia would ever examine its history. No country in Asia is willing to be honest with its history. Sonny Liew’s strong network in United States made the government of Singapore let his The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye flourished, but it’s yet to create more high-profile conversations on the history of Singapore, and the fictional Charlie Chan lives in obscurity.

G30S was meant to be a warning against communism, which, in the 1980s, is translated into any strong political ideology other than Pancasila and a stand-in for any form of opposition against Suharto and the Army. Today, however, it better serves as a warning against military fascism.

Read up on Mario’s recent trip to one of the most feminist countries in the world and follow @MarioRustan on Twitter

Comments