Last year’s Jakarta gubernatorial election has shown Indonesians how divisive and destructive identity politics can be, prompting many pundits to predict an even more vicious presidential poll next year.

Concerns over this shift have led the Center for Study of Religion and Democracy (PUSAD) of Yayasan Paramadina to commission the Indonesian translation of Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offense and Its Threat to Democracy, a book by Singaporean native and scholar on media studies Cherian George. The first edition of the book was published 2016.

“We decided to translate the book because of its relevance to our current situation,” Ihsan Ali Fauzi, Director of PUSAD, said during the book launch at EV Hive in late December 2017.

The book highlights how the religious majorities in the United States, Indonesia, and India follow similar patterns, he said. In the U.S., for instance, the Christian majority fuels fears of Islam and spread anti-Muslim rhetoric into mainstream politics. In Indonesia, Muslim hardliners oppressed other minority religions and sects. In India, Narendra Modi’s radical supporters initiate riots and academic censorship in pursuit of Hindu nationalist vision.

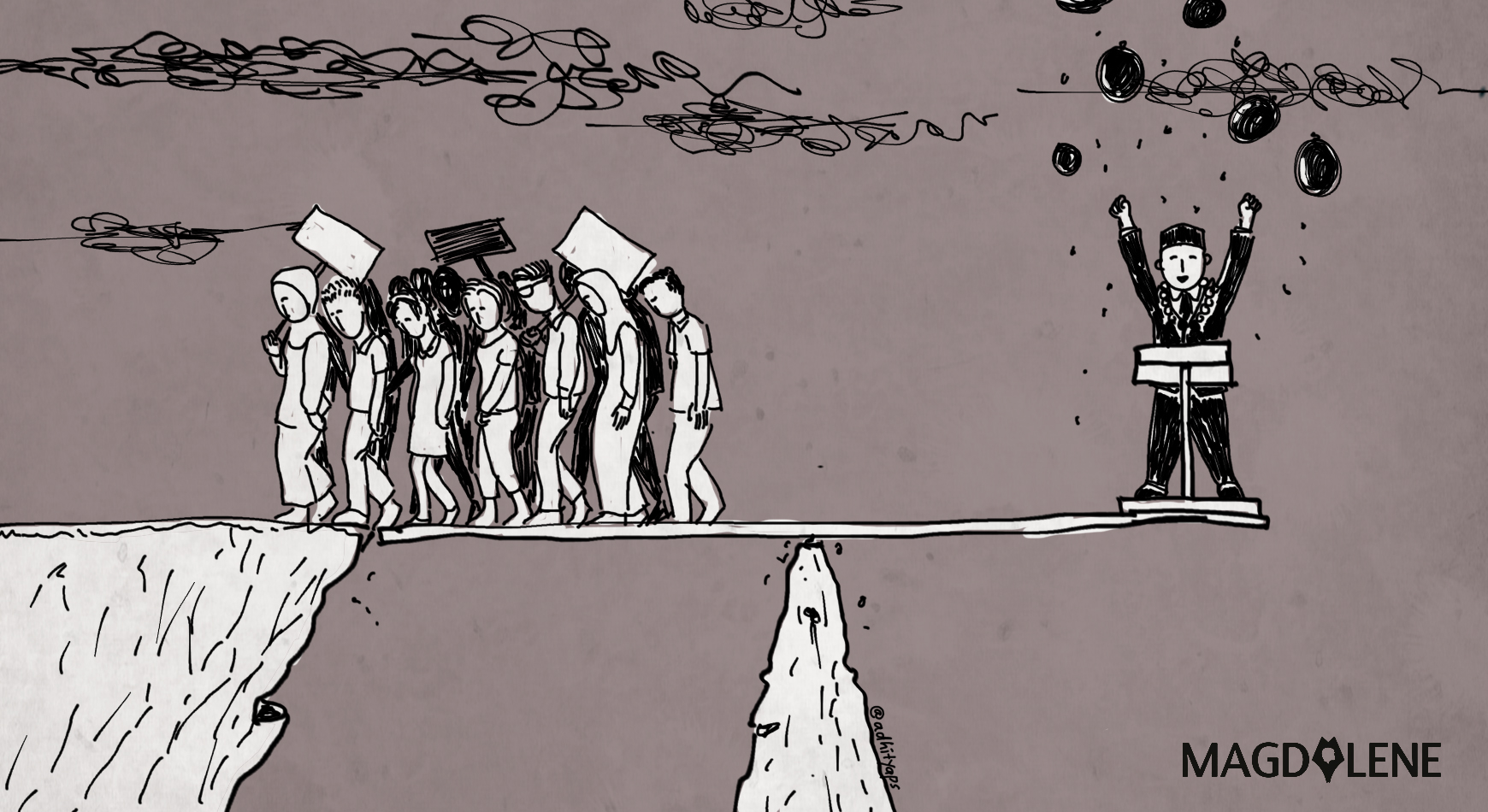

Ihsan further elaborated how Hate Spin tries to break down the way political campaigns use “taking offense” as a strategy to promote identity politics. Political opportunists exploit the democratic space to mobilize supporters and suppress the opponents, specifically by promoting political agendas that contradict democratic principles.

“Feeling ‘offended’ itself is actually a very subjective matter. It can be manipulated, it can be engineered, and fabricated,” he said, adding the strategy is often used to attack vulnerable groups.

In a research on previous regional elections regarding political supporters and violence, the center found that areas where there were tight competition between candidates and between mass organizations tend to be more intolerant and hostile during the election process. On the contrary, in areas where candidates or incumbents are likely to win by a big margin – such as Surabaya with its mayor Tri Rismaharini – elections went much smoother.

Though intolerance had always existed in Indonesia, the trend and demographic have shifted, Ihsan said.

“Now, it’s the elites that have succumbed to intolerance, and it’s getting worse because these elites have influence and power,” he added.

Endy M. Bayuni, Editor-in-Chief of The Jakarta Post, also shared his concerns about the current wave of political propaganda in Indonesia, warning that unless we do something, it might lead to “the collapse of democracy.”

Jakarta’s gubernatorial election was just the beginning and former governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama was not “the real primary target,” he said.

“They aimed to draw public’s attention and it was a successful exercise for the real battle: Presidential election 2019. I’m sure they will use the exact same strategy,” he added.

Endy highlighted an important point on Indonesia’s capability to counter the problem: “In his book, Cherian George believes in ‘self-correction’ as one of the main traits of democracy. This will take a village for sure. But, we certainly have a whole lot of instruments to counter the problem.

These “instruments” include: Article 28 of the Constitution on freedom of association and assembly; the human rights convention that guaranteed civil rights and freedom of expression including media; and the 2006 Law on Interreligious Harmony.

“We have the instrument, so it is on us whether we’re going to use it right or not,” Endy said.

Alissa Wahid, the Head of Gusdurian network that champions pluralism and daughter of the late President Abdurrahman Wahid, argued that religion was not the actual source of problem when it comes to intolerance and violence.

“It is not the religion that is dangerous, it is the exclusivity. In all religions, there will always be a group of people who promote the idea that their religion is the most of the most, the truest, the rightest. It imposes an understanding that ‘if you follow what we say, you’ll be safe and at peace, but if you won’t, you’ll be banished’.”

“This particular frame of thinking explains why the ‘majority’ may feel as if the nation belongs to them and them only,” said Alissa.

These groups equate the act of insulting hardline Islamic figures such as controversial Front Pembela Islam’s leader Rizieq as insulting Islam, thus deserving to be “hunted down.” Political parties use this opportunity for their own gain, she said, adding, “but after that, who would clean up the mess?”

The law enforcement has not been helpful in solving the problem, ignoring individual’s constitutional rights in favor of maintaining a superficial sense of peace, she said.

“Instead of standing up for constitutional rights, our law enforcement only care about maintaining the peace—that is why they tend to disband discussions if there are threats from a hardliners group,” she added.

Find out how this guy confronts Islamophobia in America one video at a time.

Comments