Now that the dust has settled, Jakartans will have to get ready to face a new future with their newly elected, though yet-to-be-officiated, governor and vice governor. Change is bound to happen, though it’s set to take place amid the remarkable resilience shown by supporters of Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) and Djarot Saiful Hidayat. And as that day looms, this great city will find itself ever more divided on social media and in real life.

What we ought to thank Ahok and Djarot for is the fact that they have succeeded in oiling the wheels of collective action and in building a tradition of trust in government like never before. The amount of social capital amassed during their tenure is both respectable and enviable.

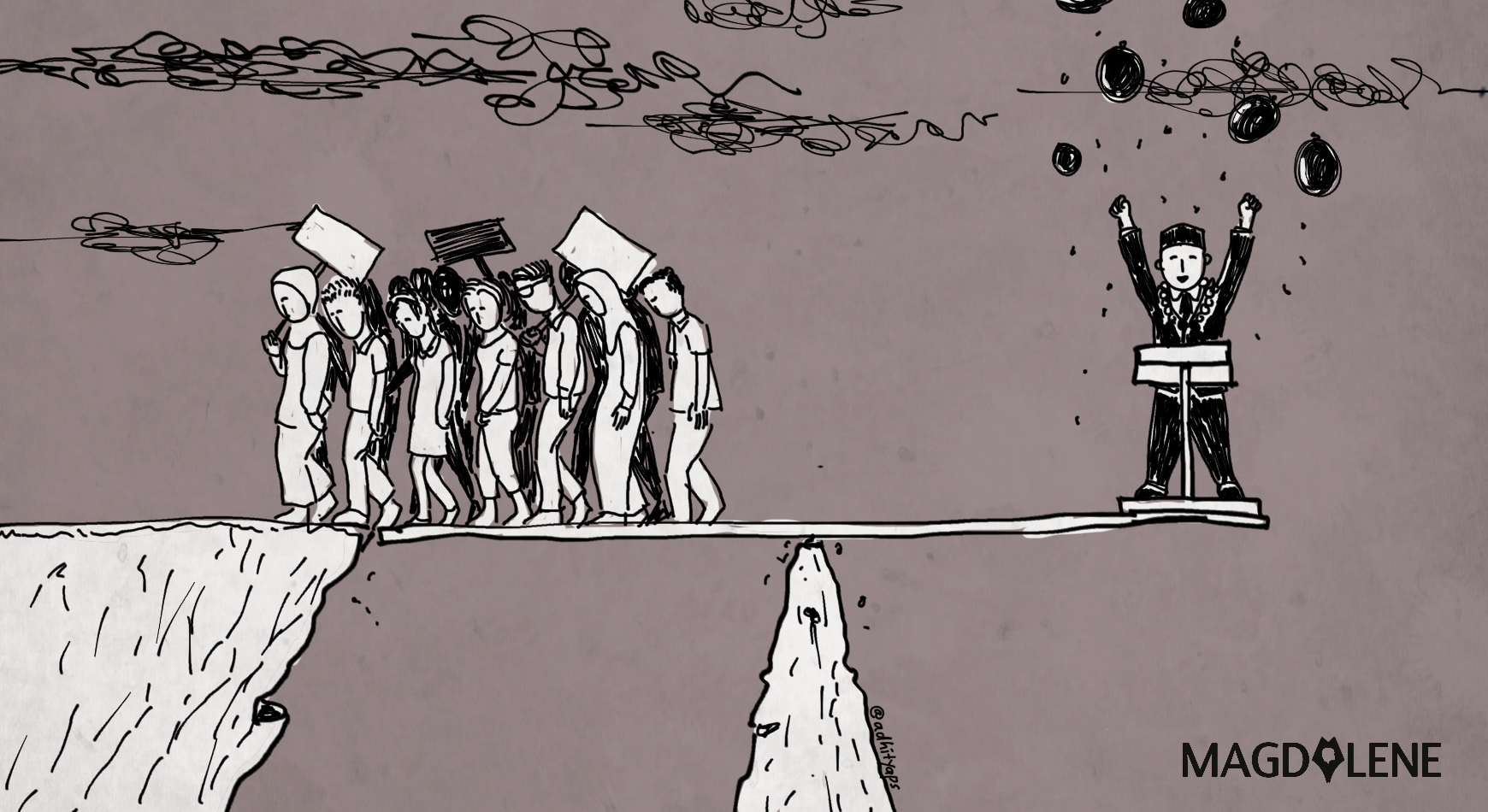

But now, having succumbed to the influence of identity politics played against a backdrop of widening socioeconomic gaps, those modern, secular dynamics will cease and give way to what still looks like an unchartered territory dominated by religious cohorts.

As we grapple with the uncertainty, two questions beg to be answered: just what kind of mark will the events of the past few months now leave on the local political culture, and to what extent will they lead to a decline in political and social trust among the people as well as falling confidence in political institutions?

Political scientists Rod Hague and Martin Harrop define political culture as “either the sum of individuals’ attitudes or as an attribute – the culture – of a group which gives shared meaning to political action”. In his book Political Culture, Political Science and Identity Politics: An Uneasy Alliance, Howard J. Wiarda ties political culture to deeply ingrained ideas, beliefs, values and behavioral orientations that people perceive of the political system, ingrained through a process.

What the recent elections have shown is an anti-thesis of the popular view in many developed countries that religious faith should have no place in debates regarding public policy. Instead, this new, budding culture feeds on religious conservatism that borders on extremism. It bids farewell to pluralism, harnesses divisiveness and provides spotlight on religious belief.

When it comes to governance, it remains to be seen where the wind is blowing. What the outgoing governor has been preaching through his application of the New Public Management theory is that running public organizations is best done through a culture of rewards and sanctions, as part of learning and encouraging people to follow the norms.

Contrary to that blunt approach, which has seen Ahok earning external praises while breeding enemy within the provincial government hierarchy, Anies’ whole campaign was based on an image of him as a religious conservative who cares for the oppressed. He’s been known to publicly ridicule Ahok’s management style, which he dubbed as a “one-man show”, but he’s also shown willingness to collaborate with those outside the public sector.

As Minister of Primary and Secondary Education and Culture, Anies Baswedan was once interviewed on his take on how to develop Indonesia’s education system. His answer back then was, “Instead of having the government solve all the problems, we should get everyone involved to discuss and find solutions together.”

Put in context, the thriving political culture that’s shaping right now is a byproduct of the major value orientations of its influencers, and it will continue to require a careful balancing act of competing political and economic interests.

Onto the next issue, regarding social trust, let us look at the finding by Kenneth Newton and Pippa Norris, who discovered that social trust and confidence in government and its institutions are strongly associated with each other. Societies need social trust to build effective social and political institutions, which leads to better government performance and, in turn, higher level of confidence in civic institutions.

In the aftermath of the elections, it seems the concept of trust has hit rock bottom.

In his popular analysis of the Jakarta gubernatorial elections, Ian Wilson aptly writes, “The victims of this politics of misdirection are those vulnerable minorities for whom the stoking of sectarian sentiments poses a very real and potentially dire threat, together with those for whom the channeling of their anger into identity politics will provide no concrete answers to the economic pressures that they face.”

In such a divided society as we have right now, where 42 percent of the population of the capital – namely supporters of the outgoing governor – currently feels somewhat disillusioned with the workings of democracy, it’s safe to say social trust is becoming elusive as threats of social vulnerability loom large.

There is no pretending. Ahok voters will never switch sides and they shouldn’t be expected to abandon their idealism. It now falls on Anies’s shoulder to reach out and prove that his victory wasn’t a setback to the great trajectory they had set their eyes upon.

Having authority doesn’t automatically guarantee that anyone can be a leader instantly, and trust is a big part of that, just as important a role it plays in the success of government policies and programs.

But as wise men say, trust is not a right. It has to be earned.

Sondang Grace Sirait is an editor and PR consultant currently based in Yangon. She’s a graduate of the University of London and Northwestern University.

Comments