A few days ago I ended my three-month internship at the Executive Office of the President. During my time there, I had the chance to work alongside the managers of LAPOR!, a government integrated platform for people to submit complaints related to public services and national priority programs in Indonesia.

Interning as a public policy specialist, I am responsible for the preparation of planning and strategic development documents. The more familiar term is research and development. This responsibility includes me being present to assist my supervisor in the meetings with the stakeholders, who were mostly officials from ministries and other government institutions.

From one meeting to another, I noticed the same pattern: women were always outnumbered by men.

In the first and second meeting I thought it was only a matter of coincidence. There could be a number of reasons why there were not very many women present. So I double checked the statistics. I was right, I thought. Based on the Statistics Indonesia 2014, the ratio between men and women who work as a civil servant was 51:49 respectively. It is not a bad number.

But then the meetings went on. After the tenth meeting, with each being held at a different government institution, the pattern remained the same. I was convinced there must have been a problem. So, I went looking for a different explanation – and found one.

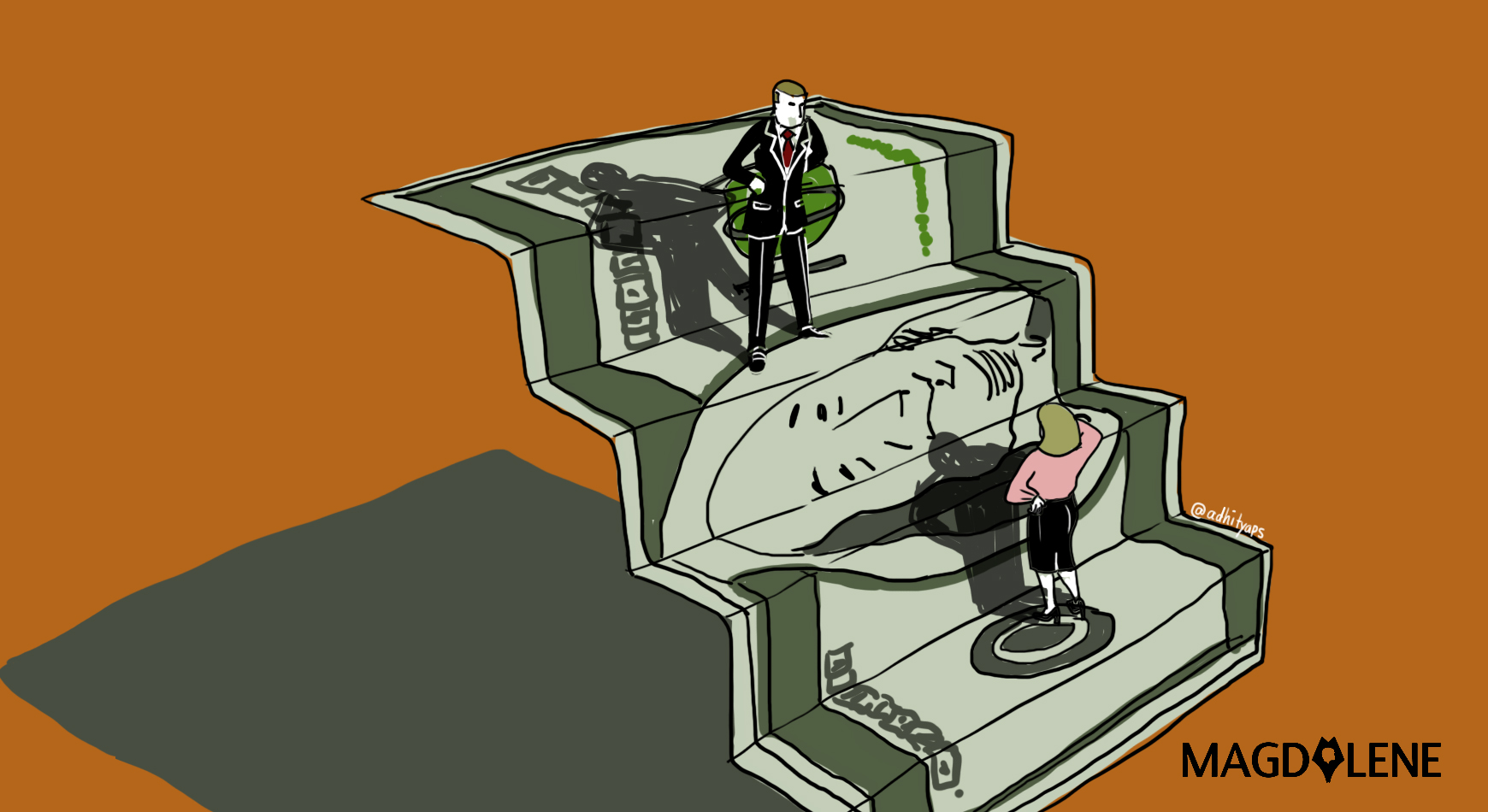

In 2014 OECD published a report stating that on average, women occupy over 50 percent of central government jobs, but only 29 percent of top management positions in the 18 member countries for which data are available. This means that although women are equally represented in terms of number, only a few of them actually lead.

I did not stop there because I knew Indonesia was not a country member of OECD, so I cross-checked the explanation with the statistics in Indonesia. It turned out that the Statistics Indonesia 2014 reported the same trend. Although we have an almost-balanced representation of men and women in functionary positions, at structural or leadership level of the government, women are still lacking.

Based on their report, the ratio of men and women who hold the position of first and second echelons – the two top structural positions in a government institution – is 4:1 and 5:1 respectively. It is from these two positions that strategic policies are often produced.

Although this is sad, it did not come as a shock to me. Indonesia has already had women quota regulation enacted since 2003. By law, each political party in Indonesia is required to field at least 30 percent female parliamentary candidates in order to participate in an electoral district.

But the laws only cover the legislative branch of the government, while the executive and judicial branches remain unregulated. Then again, a quota would not come as a solution to the problem I was describing, because it is not about number.

A 2012 report on women representation in bureaucracy by the Center for Political Studies of Universitas Indonesia indicates that there are at least three factors why women do not go as far as men in structural positions.

The first of these is the cultural factor: men do not have to go through the problem of choosing family over career, while women still do. This results in women having to make career-related decisions with much more considerations than men.

That leads to the second factor: regulation. The laws seem blind about these variables by imposing the same standards for men and women in the promotion policy. For example, out-of-town training, which is often required for career advancement, is difficult to attend for mothers who have a toddler to take care of, while it is never an issue for most fathers.

The last factor is office facilities. Most of office managements do not have the initiatives to minimalize the “double burden” borne by women. The recently issued decree of the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Children Protection that lays out clear references on how to create a gender-responsive office should be seen as a good breakthrough. We should see more of such regulation.

In the end, regulations merely work as an incentive. Regulations can solve the problem in the concrete arena, the one that is visible to our bare eyes, but may affect nothing to the perception in the back of our head.

Gender-sensitive regulations should be accompanied by the continuous effort to empower women. It is through education that we can grow the confidence of women to lead as well as to erase the stigma that women are unable to create strategic decisions in the government, thus enabling them to actually run the office.

Nesita Anggraini is a final year law student in Indonesia. She’s currently writing her thesis about data openness in the government.

Comments