Last year, I met an Arab man in Adelaide and I introduced myself as an Indonesian Muslim. This encounter quickly got interesting. We had an hour of heated discussion, during which he strongly criticized me for not wearing the hijab. He argued that as a Muslim woman, I must wear the hijab, because it is compulsory.

Muslim women without veil are “less pious”, “incomplete” or “less beautiful” than those who wear the hijab, he said. I told him that I could not accept that people can judge someone's piety based on the clothes they wear.

Several weeks later, a few friends from a socialist group invited me to join a rally to protest the promulgation of terrorism laws in Australia as it discriminates against the Muslims, especially those who wear the veil. I saw the same man among the protesters and we smiled at each other.

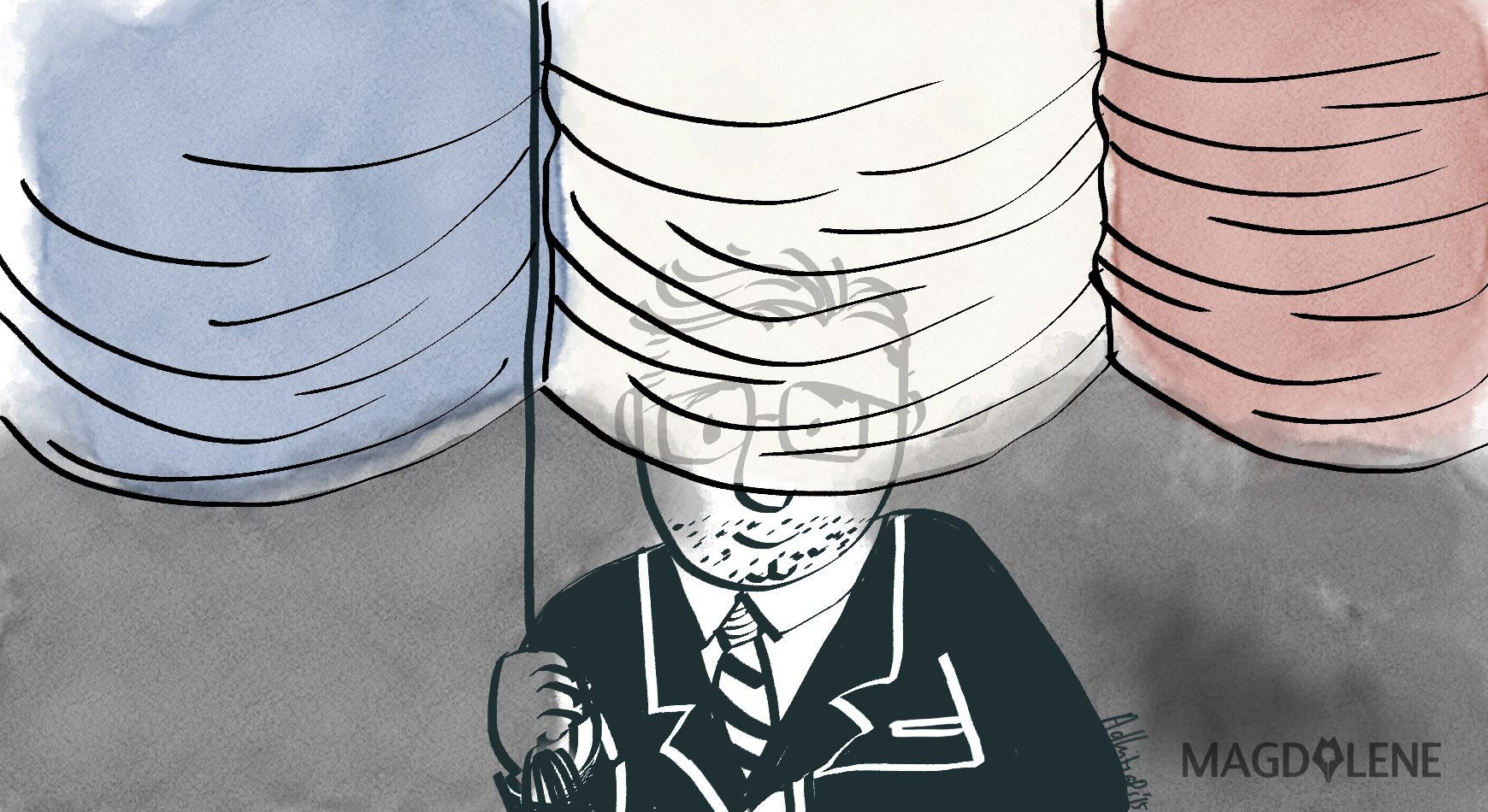

Early this month, we read about the Paris bombing attacks that have caused so much anguish and sorrow across the world. The world reacted strongly, as reflected not only by the French flag filtering so many profile pictures Facebook, but also by the debates these sympathies stirred up. Personally, this reminded me of my encounter with the Arab man.

In Indonesia I observed the emergence of two “dichotomous” camps. The first camp is made up of those who post the French flag-colored profile picture – those accused of standing by the side of the West while ignorant of similar sufferings outside of Paris. The second is those

who refuse to have any “signifier” in expressing their response – those who criticize the decision of the other camp.

For me, it is apparent that the problem lies in how we present our sorrow and sympathy on social media over the Paris attacks. Is it really a free choice when it involves the media?

Before we look further at this issue, we need to stop the perception that criticizing the decision to put the French flag-filtered photo means to doubt anyone’s sincerity in compassion and solidarity. This is, rather, to look closely at the impact of the uniformity of the profile photo as the “signifier” representing people's sorrow in this unequal, diverse world.

We cannot consider the media innocent when it comes to representations, particularly in social media, which has a global, cross-bordering coverage. Academic works prove this. Edward Said argues that the Western media have distorted the image of Islam by portraying Islam as oppressive, outdated and causing many conflicts. Similarly, Lila Abu-Lughod criticized the Western media for misrepresenting Afghan veiled women under the Taliban as lacking of agency and in need of saving from the West.

The French-flag resemblance is unavoidably viewed as a symbol of the West. This image is inseparable from Said's study regarding Orientalism, which shows us the strong role of British and French Empire in perpetuating Western imperialism through literatures, scholarships and system of knowledge. Indonesia’s founding president Sukarno emphasized in his opening speech of the Asian African Conference in 1955 that “colonialism has also its modern dress, in the form of economic control, intellectual control.”

With the long history of Western colonization in Indonesia, setting the French-flag resemblance as a signifier of our grief for Paris attacks as well as other tragedies of humanity in the world is definitely problematic and unwise. However, we also must be careful not to reduce it into cultural relativism or “anti-West” sentiment. We need to deal with our cultural diversity without indirectly mainstreaming ethnocentrism or some misleading views – such as one that says feminism is a Western-invented concept, so it is considered completely incompatible with our culture.

Meanwhile, we also cannot disregard what the other camp is concerned about. By posting the three-colored flag they want to show their solidarity and, at least, that as Muslims they also condemn such attacks: Islam is a peaceful religion. Apart from that, we also cannot dismiss the anxieties over religious intolerance and radicalization in Indonesia, including the concern on Arabization of Indonesian Muslims.

We must not forget – and here I’m recalling my discussion with the Arab man – the church burning in Aceh Singkil, the anti-Ahmadiyah sentiment, the eviction of Sampang Shiite community, the attack of the place of worship of an indigenous religion in Central Java, and the Joint Ministerial Regulation 8 & 9/2006 on Places of Worship that has led to discriminative policies on building places of worship.

What might be overlooked is that our expressions of grief were not made in private space, but in a public media with a global scope.

Promoting this uniformity of symbol or representation on the media has the potential of committing further violence by creating a new axiomatic signifier of our humanity and sincerity by silencing and othering various expressions of those in different socio-historical contexts throughout the world.

The heated debates over how we represent our sympathy over the Paris attacks unfold the real complexities in dealing with our own humanity and subjectivity. People's subjectivities are as diverse as their historical and cultural contexts. Creating a universalized, uniformed symbol of humanity, unfortunately, will bury the innumerable symbols as well as the essential state of humans who have plural standpoints.

The debates hopefully give us a moment to look in the mirror, finding the reflection of our own image, and standing up with our own subjectivity. This is the moment when we can begin to change what the (social) media represents, to be as diverse as our standpoints.

I would not suggest that we stay silent when we clearly have something to say and let our experience be misrepresented, or, again, fall into the “old” dichotomous landscape of media (mis)representation: the West against the rest. With inequalities affecting our lives and with the socio-historical burden we carry, we need to find some ways to represent our diverse subjectivities as well as to save our humanity.

A. Ambarwati is a graduated in English Studies at Universitas Padjadjaran. She is interested in the issues of culture, development and gender.

Comments