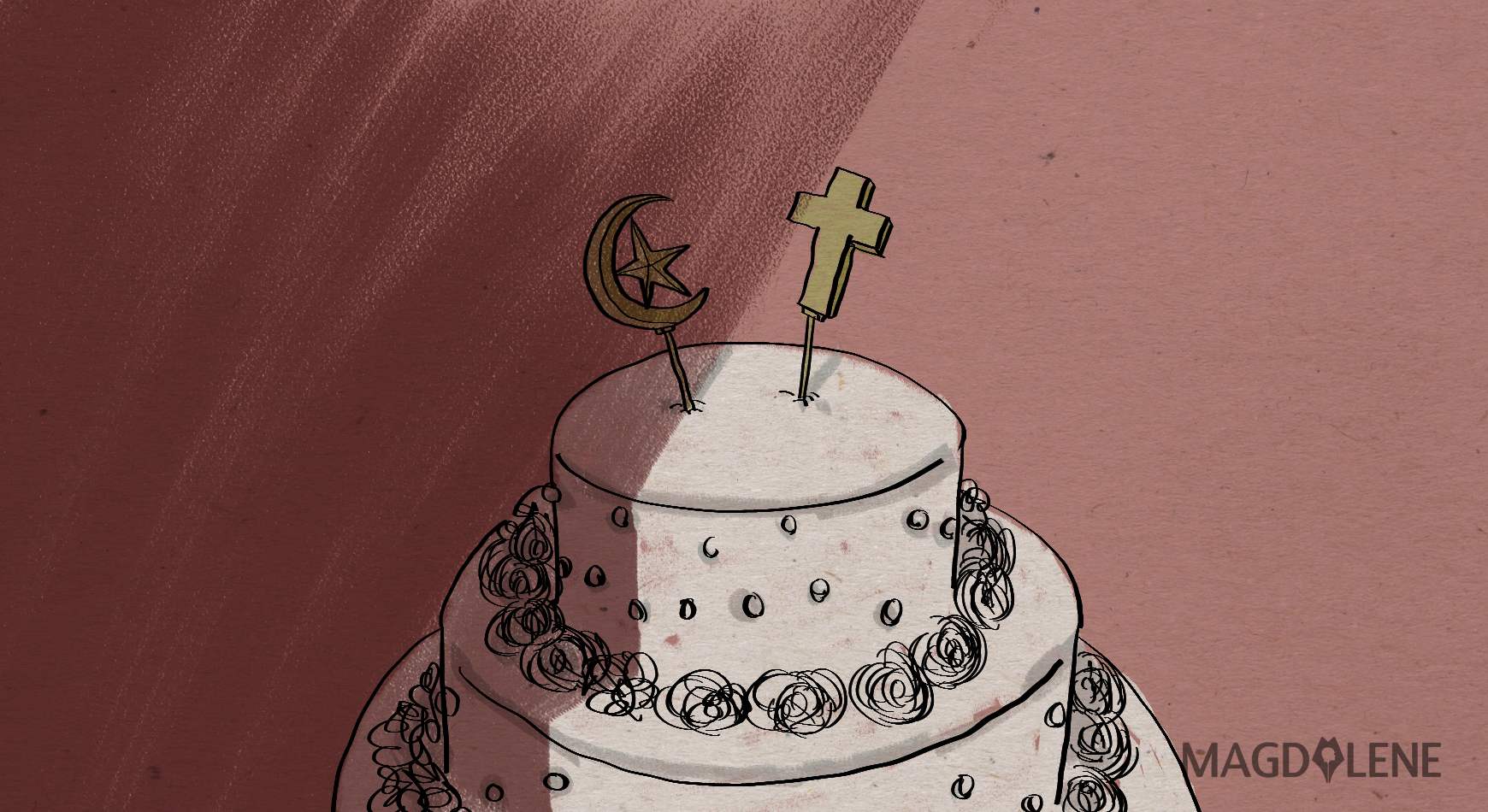

I live in a country in which the government tends to get in people’s business when it comes to certain private matters, like regulating whom they should or should not marry.

The day my boyfriend and I decided to give our interfaith relationship a shot, I told him, “We’re basically heading towards a solid wall.”

The “wall” is the 1974 Marriage Law, which has for many decades made it very hard for couples like us to marry in Indonesia. It’s not that nobody has tried to break this wall. Last year, a student and four graduates from the School of Law, University of Indonesia proposed a judicial review to article 2, paragraph 1 of the law. The petitioners demanded the court give a new interpretation to the section that defines a marriage as legitimate only if it’s officiated according to the religion of the bride and groom. They argue that the law violates Article 28 E of the same law, which stated that everyone has the freedom to worship and practice their chosen religion.

For a long time the interpretation of marriage has left many interfaith couples with these options: break up, convert to the other’s religion, or get married overseas, because religious clerics tend to require the bride and groom to be of the same religion. This, according to the petitioners, deviates from the essence of the law, so they demanded that the Constitutional Court evaluate it.

Their argument has been pretty much dismissed by the government. Staff Expert on Law and Human Rights Machasin said passing the petition meant risking disharmony in the predominantly Muslim Indonesia.

Last week, the Constitutional Court rejected the judicial review, citing reasons such as respect and recognition of “others’ rights and liberty”, the fulfilment of justice that “fits moral and religious values”, and the maintenance of security and public order.

Is this not the most warped justification you’ve ever heard?

First of all, justice is universal, while “moral and religious values” are subjective. Secondly, it is NOT okay to sacrifice some basic rights just to keep things in order. How about finding a middle ground? And, thirdly, what’s with the pessimistic outlook? Does the government really believe that we Indonesians cannot behave, that such a personal matter as nuptial affairs can pose a threat to national security? And what then is the State’s role if it cannot maintain order in such an ethnically and religiously diverse nation?

Maybe interfaith relationships are not for Indonesians, because our slogan Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (unity in diversity) is just that, a slogan – as much a myth as Garuda, the national symbol.

Constitutional Court Justice Arief Hidayat said, “Based on our Constitution, Indonesia is neither a Muslim country, nor a secular country. Our foundation is Pancasila, which stipulates that the belief in One Almighty God should be applied to our social lives.”

In other words he said those who marry people from different religion in either none or more than one religious rituals (as some interfaith couples resort to do when they wed) are not faithful to Pancasila. This is where I think the State is interfering too much on the relationship between the people and their God.

The state should guarantee the rights of its citizens as long as they have already chosen one of the six recognized religions. Pancasila is not an excuse to decline interfaith marriage because, in theory, as our individual state-ID shows, everyone believes in One Almighty God. But one’s God just might be different from another’s.

I believe the State should allow interfaith marriage to be registered and leave it to individuals to observe their own religions. Otherwise, they should just say it bluntly to avoid ambiguity over whether the state can or cannot legalize interfaith marriage. They might as well say, “Interfaith couples may leave the country and get married elsewhere. Those who don’t have the courage and money to do so should just suck it up and suffer in silence, because this is how we roll.”

But it’s not just the government, many people still find interfaith marriage unacceptable, or they find it suspect. Media reporters asked one of the petitioners, hijab-wearing Anbar Jayadi, if she proposed the judicial review because she wanted to get married to her boyfriend, who is of a different religion.

Anbar responded, “No, I don’t have any boyfriend. I’m still single, but none of us know whom we will meet, fall in love with, and marry in the future. That is why we need the state to guarantee our rights so that we can have a clear legal status in the matter.”

The media’s presumption that she was motivated by her own personal agenda, instead of the desire to review the law reflects the way our society works. Because of religious bias, not very many people are acquainted with the idea of interfaith marriage. Even harder to change than the law are norms.

The popular notion is that partners of different faiths makes a marriage more prone to conflict and separation than marriages of the same religion, but this is a hasty generalization. I’ve known many interfaith couples who work it out just fine. I believe that each couple has their own dynamics. Yes, religion might be a significant factor, but it’s not the only determining aspect that contributes to a successful marriage.

I’m not married myself, but learning from my parents and many married couples, I believe the key to a succesful marriage is good communication that should be cultivated even before the wedding. The couple should be willing to discuss and compromise in decision making about all matters, including whether or not they want to have children, and, if there will be children, how they will raise them, and so on, in order to minimize potential disagreement in the future.

But I haven’t lost hope. Although the judicial review was rejected by the Constitutional Court, change is possible if we keep trying. It might be challenging, but it’s not impossible. There are also groups who offer to facilitate interfaith relationships such as nikahbedaagama.org.

We are pretty lucky to have people like the petitioners who care about changing legislation to improve our country. At the end of the day, it’s our responsibility as Indonesians to be critical of laws that are no longer relevant and that need to be re-evaluated. We can actively initiate, participate, and contribute to change by supporting various causes, maybe starting with online petition.

As for my boyfriend and I, we're not backing down yet, not before we even reach the battlefield, just because things look rather knotty from here. Breaking the wall is never easy, so we better start drilling now.

Comments